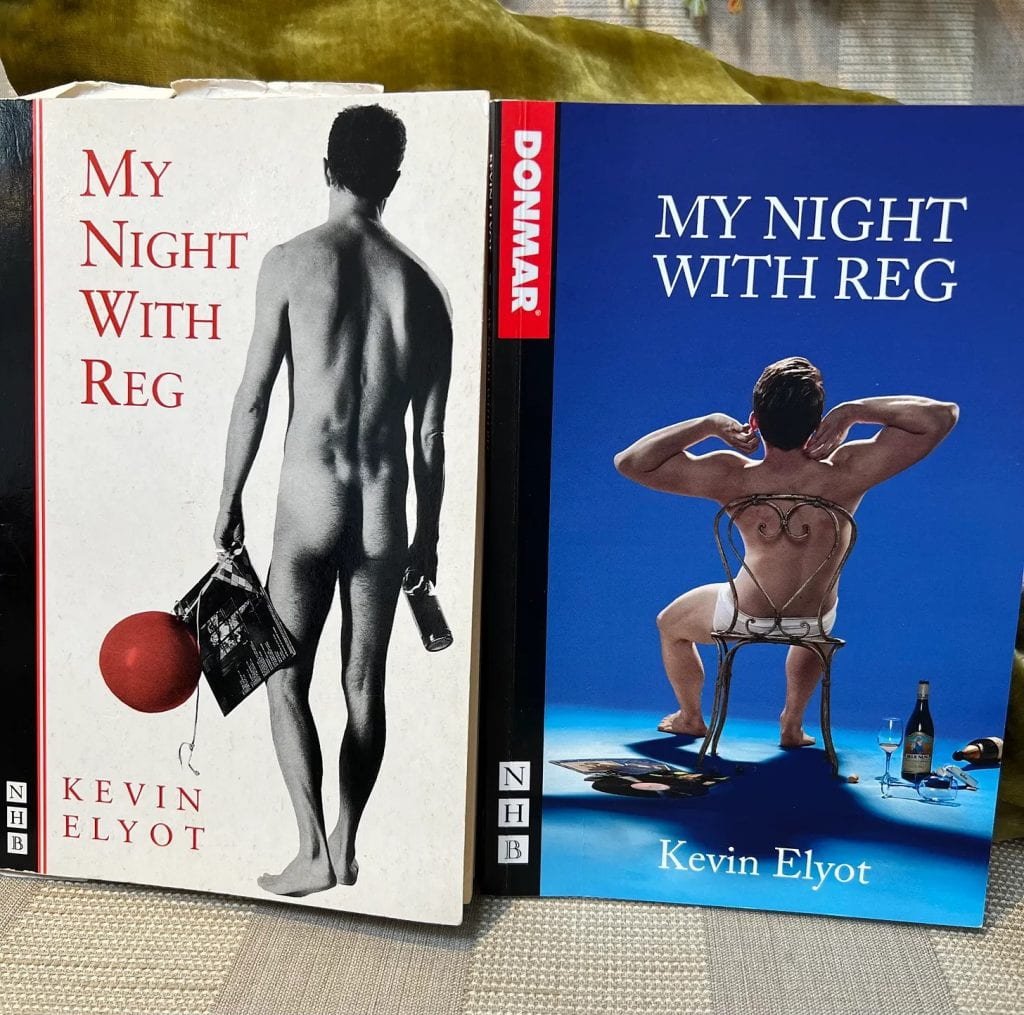

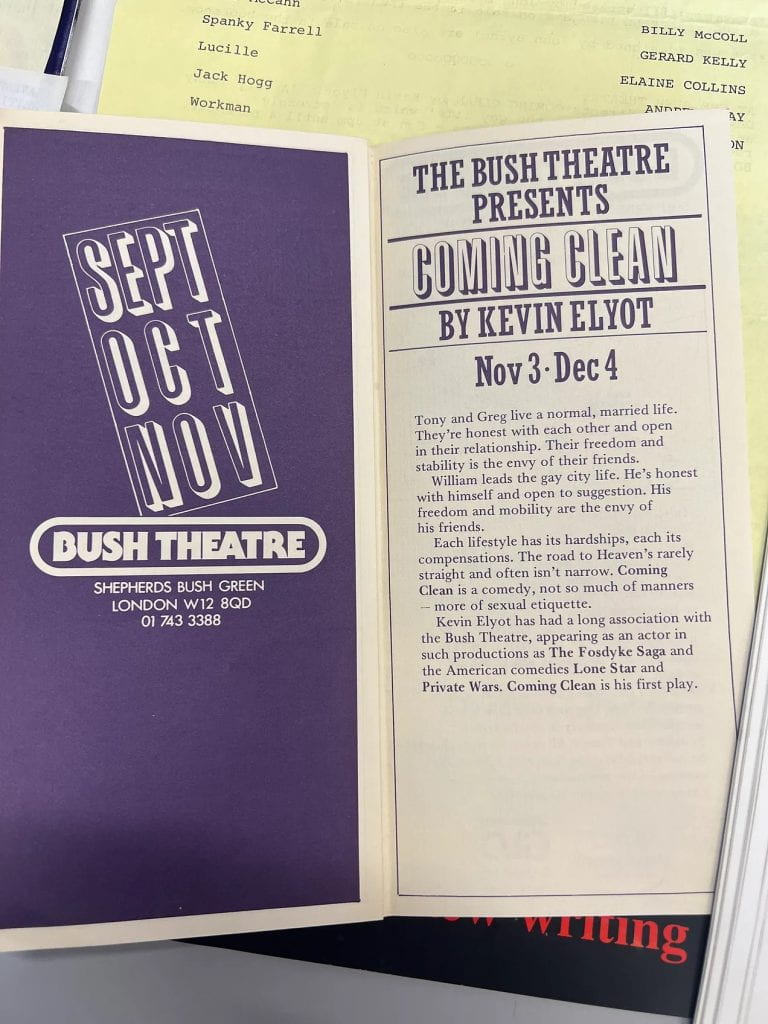

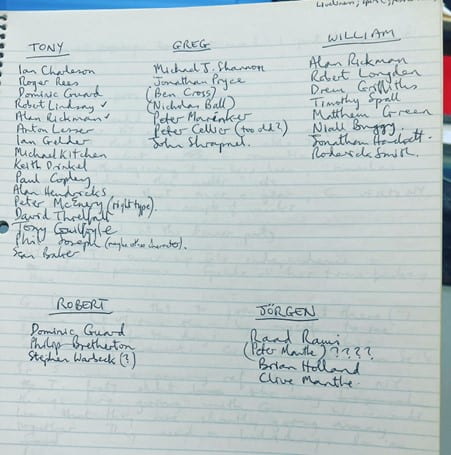

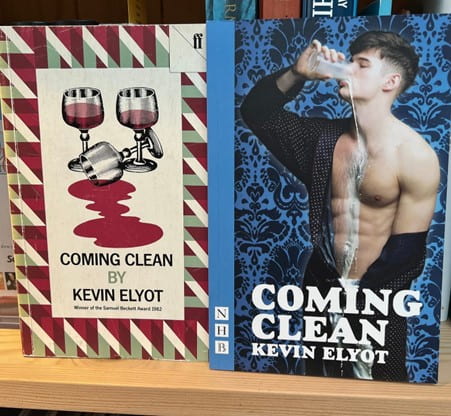

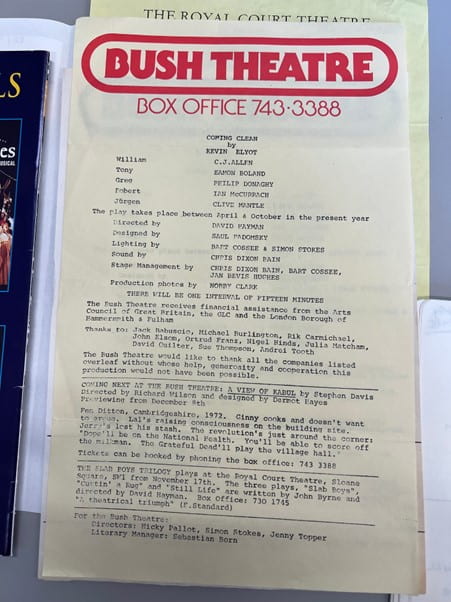

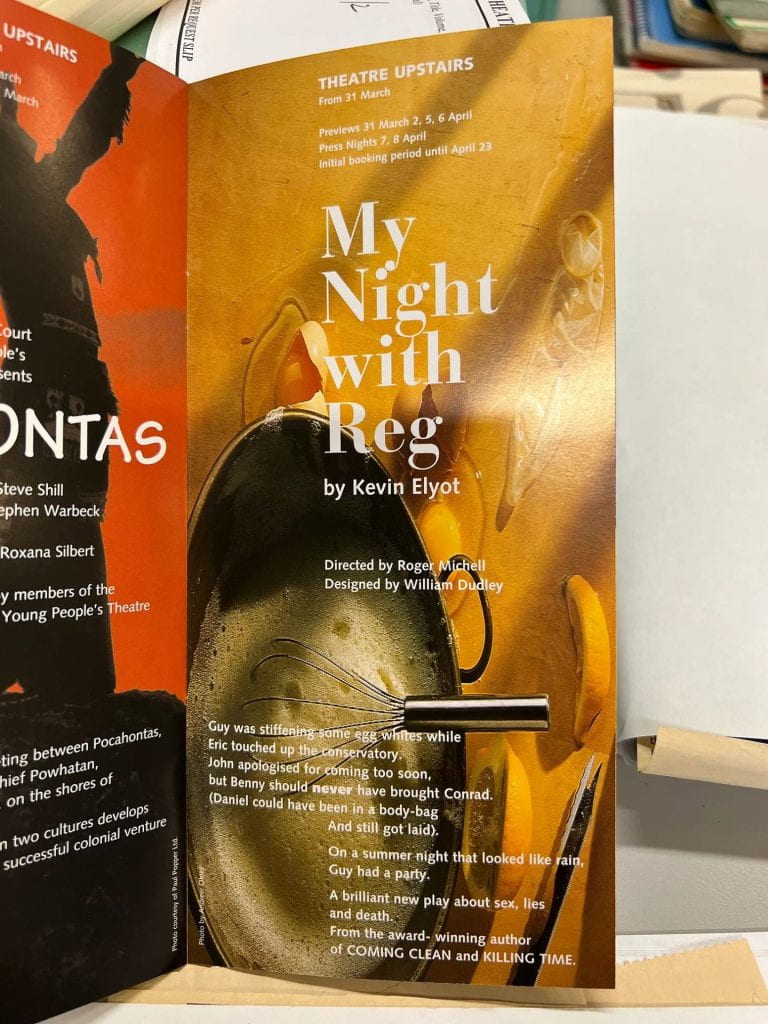

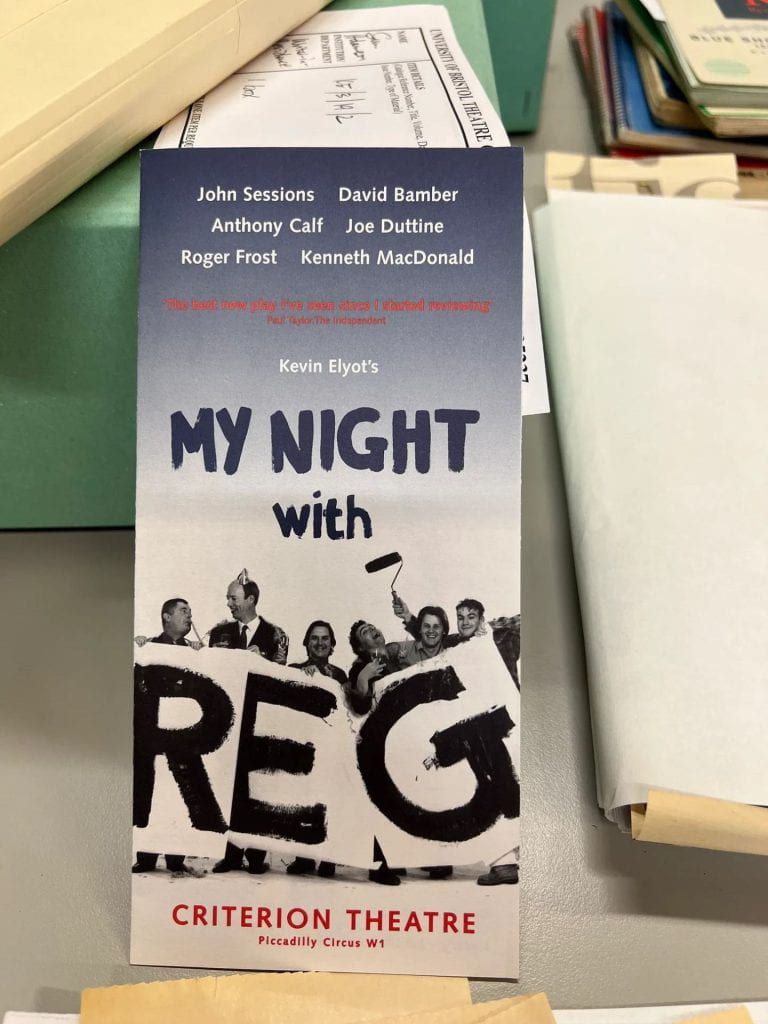

As a writer-in-residence at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection, I’ve spent time researching the papers of the playwright and screenwriter Kevin Elyot (1951-2014). Here is my fifth article in response to Elyot’s archive, in which I discuss his fourth play Mouth to Mouth. A general reflection on Elyot is here. I’ve also written about Coming Clean (1982), My Night with Reg (1994), and The Day I Stood Still (1998).

My year with Kev: moral questions

My stated aim to the award’s panel was to write about Elyot – but I’m a playwright, not a biographer, and the first question was, simply, is this right?

Elyot was guarded about himself in interviews, and, as his agent Sebastian Born told me, did not share early ideas or drafts with others:

Kevin’s plays always arrived fully formed. He was superstitious about saying anything about what he was working on, so every once in a while I would receive a brown envelope containing his latest play. Such a thrill for an agent.1

Not unexpectedly, the archive reveals things Elyot withheld from journalists, as well as the hard work – pages of notes, multiple drafts – behind those ‘fully formed’ plays. With his notebooks, letters, research materials, press cuttings, and photographs, I was privy to some of Elyot’s innermost fears, tastes, resentments, pains, joys – and some of his personal opinions on friends and collaborators.

I was able to quell my unease about this strange intimacy with Elyot fairly quickly. I assumed that had he not wanted people to make discoveries about his life and practice, he’d have destroyed his papers. Besides, the yearly award – funded by an endowment given to the University of Bristol by members of Elyot’s family – exists to inspire writers in their own practice. It asks them to consider not only Elyot’s published and produced work, but the life and work behind that work. The materials are there to be read, and I began to understand the award as an act of artistic serial reciprocity, a tip of Elyot’s cap to succeeding generations.

The second moral question was how relevant are Elyot’s papers to my understanding of his performed and published work?

It’s obvious that Elyot drew from personal experience to write his plays, and there’s a lot in his notes about what he intended the plays to do. So it’s tempting to disregard the biographical and intentional fallacies – those (in my view) sound and helpful twentieth-century critical theories – and read the work via the life. Elyot argued in a column in The Telegraph in 2001 that if art reflects the artist, ‘this is only part of the story,’ yet at the same admitted,

Whether a play is about a schoolboy love affair or a satire on the power of the multinationals, it will only work if the writer taps an emotional core and thus, to some degree, reveals himself.2

The central character in Elyot’s fourth original play Mouth to Mouth is a playwright called Frank. When asked by the journalist Heather Neill at the time of the play’s premiere in 2001, ‘does Frank equal Kevin?’, Elyot could not quite deny it:

That’s a difficult one. Everything I write is a bit autobiographical, but I’m in all the characters.3

His piercingly honest, funny, moving and often troubling plays simply have the feel of being personal.

In the end, I decided to make myself comfortable on the fence. Sometimes Elyot’s papers elucidate the work, but the work stands on its own. On the one hand, I prefer to look at texts as texts – on the other, these articles are the reflections of a playwright, not academic research papers, so I don’t have to take any notice of the biographical and intentional fallacies.

All I’ve been able to do, as someone who admires Elyot’s writing, is reread his published plays, immerse myself in his papers, and call it as I see it.

As I see it, his archive reveals two key things about Elyot.

‘The usual’: undisclosed emotion, frustrated desire

The first is that his notes are not dissimilar from his six original plays, in that there is a steady repetition of ideas. As I’ve written elsewhere, Elyot was a hedgehog of a playwright, a Proustian obsessed with the same themes: the recovery of the past, repressed desire, the Forsterian need to connect, music, betrayal, guilt, mortality. In an early notebook for The Day I Stood Still, he wrote:

A tragedy interrupted by life’s vulgar comedy.

Show

inhumanity bleeding.Painful.

Undisclosed emotion.

Frustrated desire.

The usual!4

Because he was preoccupied with ‘the usual,’ his projects intersected, and some notebooks resist the archivist’s ex post facto categorisation. Elyot’s method, in his own words at the time of Mouth to Mouth, was ‘to make lots of notes over a long period. Hopefully something emerges that I can fashion into a play.’5 He discussed this process more expansively with Harriet Devine in 2005:

DEVINE: […] how does it happen that an idea for a play comes along? Is it always the same process? Does something happen that sparks it off?

ELYOT: It might be a moment that intrigues me, or – it can start off in the oddest way. And really it makes me sound a bit capricious and maybe rather shallow because, while some playwrights might sit down to write a play about Guantanamo, or the Health Service, I tend to write a play because I want to see two people doing a tango, or want to hear a piece of music in juxtaposition to something else. And then gradually you put pieces together over a length of time, and shape something out of it.6

Elyot’s reworking of the same themes – not ‘shallow’ themes, yet not overtly political ones – combined with his process of starting with ‘fragments’ (Devine’s word), meant that plays developed concurrently. In a notebook assigned by the Theatre Collection to The Day I Stood Still, he wrote in capitals, ‘WRITE TWO PLAYS!’, and although the play he developed in this book is indeed The Day I Stood Still, many of its ‘fragments’ form the basis for his next play.7 Early on he wrote, ‘Wife: Lindsay’ – a reference to his friend the actor Lindsay Duncan, for whom he created the part of Laura in that play, eventually called Mouth to Mouth.8 A few pages later, he wrote:

THE STORY:

X. falls for son of friends (wife + hubby). Starts rel. underage. So X. is having son. Wife’s having affair.9

Here, Elyot discovered the essential plot of Mouth to Mouth – the secret betrayal by her gay best friend of a wife who has her own secret – as he shaped The Day I Stood Still.

Vulnerable playwright

Elyot was, I think, self-conscious about ‘the usual,’ aware that to plough the same territory over and over was to risk not discovering new story treasures, and to risk being criticised for repeating himself.

In a Day I Stood Still notebook he wrote, ‘Squash all opposition with some big, assured laughs + bold dramatic strokes’ – his apprehension about ‘opposition’ is revealing.11

A galvanising message to himself in a Mouth to Mouth notebook is wise, and inspiring to anyone who reads it. But there is a poignancy to it; in my view, only a vulnerable artist could have written it:

FORGET FASHION, what’s expected, comedy per se, rivals – WRITE what’s true, what’s true to you, ignore EVERYBODY, write a TRAGEDY, reach for the truth of life, aim high, write a masterpiece. Amaze + surprise them.12

Mouth to Mouth: a moral question

Wonderfully, Elyot, a gay, HIV-positive playwright, a waspish and quick-witted Proustian who was nevertheless insecure about his writing and worried about repeating himself, harnessed his insecurity and experience of chronic illness to write a masterpiece about – I want to groan, and yet! – a gay, witty, insecure, HIV-positive and Proustian playwright, who, suffering from writer’s block, laments to Laura (his best friend, that ‘Wife’ in the The Day I Stood Still notebook) that he is ‘always being accused of writing about the same thing.’13

I suggest that any blocked and/or insecure writer reading this should refrain from taking heart from it: surely no one should write dramas about not being able to write. Yet somehow, with Mouth to Mouth, Elyot produced a stylish, droll and deeply disturbing meditation on a moral question: should writers draw from real life? Can they, if it involves betrayal of loved ones? Can writing only ever be a sharp practice?

The play has a palindromic structure and begins with a scene in which we glean that something terrible has happened – ‘unimaginably tragic’ as Frank says later – and that Frank has things he needs to confess to Laura.14 We flash back, then forward, to discover what these things are – and that everyone, not just Frank, has his or her own guilts and secrets.

In the final scene we return, according to a palindrome, to the first scene, and climactically get the answer to the question we have seen Frank grappling with throughout: should I use my life, the things that have happened to me and that I have made happen, to create my art?

In one reading, the answer is no: Frank will not plunder his life, and will not exacerbate the trauma of his best friend Laura, whose son, we now know, has died in a dreadful accident.

But human beings are complex creatures, and though he says he wants to, Frank never confesses his secrets/sins to Laura, perhaps in part because without her knowledge he discovers the secret of her affair. Typically for Elyot, there is more than one reading.

For a late draft of My Night with Reg, Elyot used two epigraphs: a passage from Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s posthumous novel The Leopard, which survived into Reg’s published edition; and a passage from Patrick White’s 1976 novel A Fringe of Leaves:

‘… Would you not say that life is a series of blunders rather than any clear design, from which we may come out whole if we are lucky?’15

Elyot dropped the White from Reg’s rehearsal draft onwards, but it was a very interesting idea, because the play and all of Elyot’s subsequent plays including Mouth to Mouth are scrupulously well-designed, yet peopled by characters blundering through life, barely coming out whole. The design of art can (should?) be elegant, but, first-rate playwright that he was, Elyot was utterly fearless when it came to the messy ‘truth of life’ for the characters inside his design – Truth as Hilary Mantel sees it in her memoir Giving Up the Ghost:

Truth isn’t pretty […] and the pursuit of it doesn’t make pretty people. Truth isn’t elegant; that’s just mathematicians’ sentimentality. Truth is squalid and full of blots, and you can only find it in the accumulation of dusty and broken facts, in the cellars and sewers of the human mind.16

Mouth to Mouth’s epigraph is from the final volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time:

The whole art of living is to make use of the individuals through whom we suffer.17

and this lesson becomes a lifeline for the dying playwright Frank, who’s known, if he’s known at all, for a play about Proust called ‘A Piece of Cake’:

What happened [to Laura’s son] – was just awful – unimaginably tragic. It’s haunted me for a year. And the point is – I think it’d make quite a good play. You see, I’m coming round to the opinion that I have to use whatever’s thrown at me.18

Showing how it goes

I don’t lead a life full enough to be able to write several plays about. I don’t do that much, and my daily routine is pretty boring, so I can’t be writing about that. It would be very dull to sit in a theatre watching it unfold. The key is to try and enter the world of the imagination.19

Yet the anxieties Elyot expressed in his notebooks about repeating himself with ‘the usual’ and running out of ideas, and even the point he made to Aragay and Zozaya about his uninteresting life, turn up in Mouth to Mouth:

FRANK: I’m finding it [writing] pretty difficult, to be honest. I can’t put my finger on why exactly –

LAURA: No ideas.

FRANK: That could be it. But no, I’m having quite a hard time. I’m always being accused of writing about the same thing.

LAURA: And what would that be?

FRANK: Well, me, as it happens, which simply isn’t true. They say it’s a sign of creative bankruptcy.

LAURA: I’d have thought personal experience was the only thing worth writing about.

FRANK: But my life isn’t that interesting, and if it were, I wouldn’t have the time to write about it.

LAURA: Oh, I do wish tonight weren’t happening!

FRANK: Yes, well … Nice olives.20

In a lesser writer’s hands, these writerly anxieties might bore or irritate, seem like so much authorial moaning. But Frank is more complex than he appears – and I love how, as in Chekhov, his complexity is conveyed partly by the hilarious indifference with which he is treated by others. The exchange ‘Oh, I do wish tonight weren’t happening’ and ‘Yes, well … Nice olives’ is typical: we know there’s a world of torment and doubt inside Frank because Laura doesn’t really care and Frank must turn to the subject of olives.

All of Elyot’s dialogue is like this: crisp, funny and, most importantly, full of subtext. It is never self-righteous, but it demands its audience interrogate knotty moral questions and not-pretty truths about human beings:

We lie.

We are duplicitous.

And the artists among us are impelled by nature to use whatever treasures they find in their territory to create their art.

‘I wouldn’t dream of preaching,’ Elyot said, ‘I just show how it goes.’21

This work was inspired and developed through the generous support of the Kevin Elyot Award at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection.