As the 2023 Kevin Elyot Award writer-in-residence at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection, I have written a series of articles on the original plays of the playwright and screenwriter Kevin Elyot (1951-2014). Here is my third, on his second and most famous play My Night with Reg. A general reflection on Elyot is here. My piece on his debut play Coming Clean (1982) is here.

Rejection and triumph

Set in the 1980s, it is a tragicomedy about seven gay men in North London living in the shadow of Aids. One of them, Reg, never appears though his impact on the others is profound – a Waiting for Godot-like conceit in a play built upon several elegant formal conceits.

Elyot was commissioned to write the play by London’s Hampstead Theatre, but in mid-1993 it was rejected: my analysis of that rejection, according to my reading of the relevant documents in Elyot’s archive at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection, is here.

Since I wrote that piece, Sebastian Born, Elyot’s agent, told me that a reading of the play at Hampstead was ‘for some reason the worst, flattest experience of any reading I’ve ever attended.’ After Elyot and Hampstead parted ways, Born ‘tried to reassure a depressed author that there would be interest elsewhere.’ He sent the play to the Royal Court Theatre, then under the artistic directorship of Stephen Daldry, and a few days later, the literary department expressed an interest.1

On 31 March 1994, My Night with Reg premiered at the Royal Court’s Theatre Upstairs in a production directed by Roger Michell.

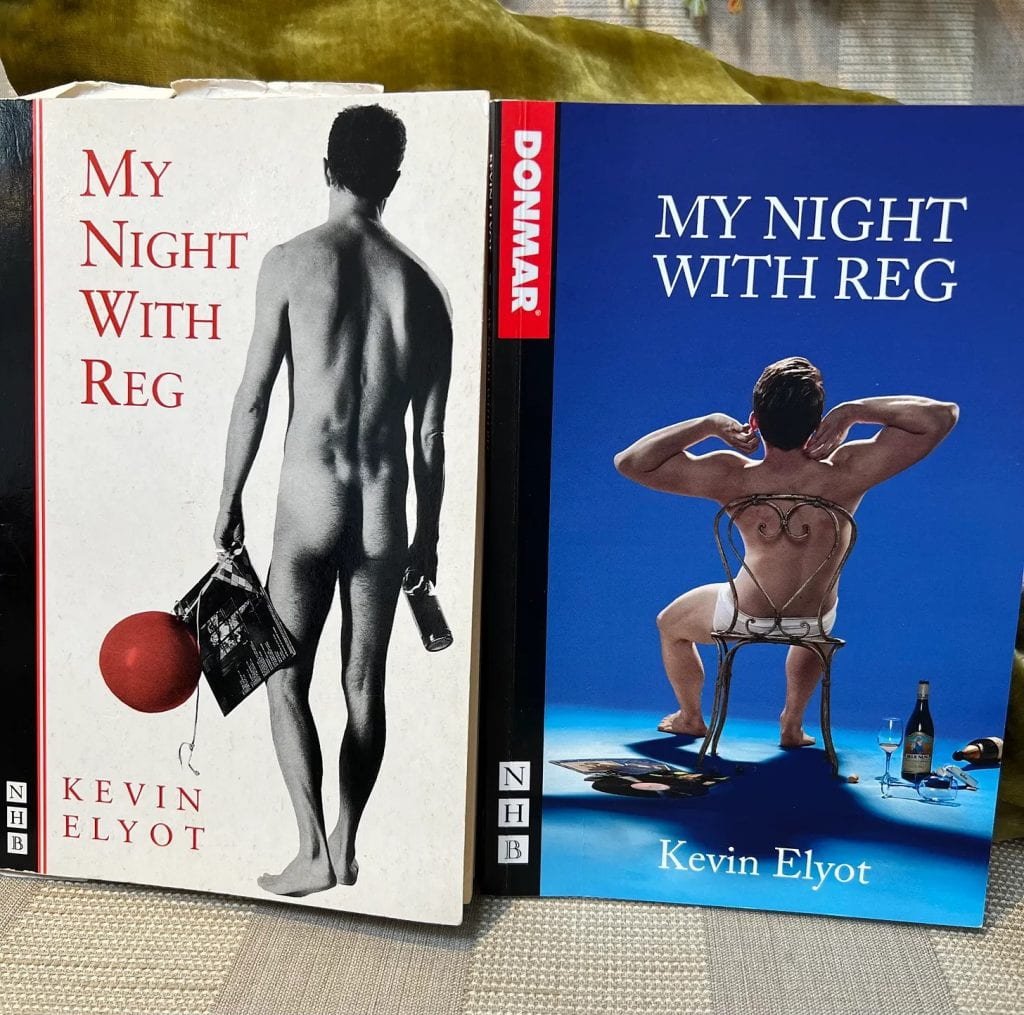

It was critically acclaimed, transferred to the Criterion Theatre in the West End, published by Nick Hern Books, garnered Elyot the 1995 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Comedy, and was filmed for the BBC by Michell with its original cast.

The play: a play with time

In Scene One, old University of Bristol friends Guy, John and Daniel (the allusions to Elton John are deliberate) gather for a housewarming at Guy’s flat. When Daniel leaves, John confesses to Guy that he is having an affair with Reg, Daniel’s boyfriend, who is due at the housewarming. This is a terrible blow to Guy, as he harbours a secret love for John.

With Scene Two comes the first of two coups de théâtre, and Elyot’s own words in one of his notebooks can convey it:

at the start […] we think it’s the FLATWARMING, but are jerked on a year or so to realise it’s a WAKE + Reg’s at that!!!2

Reg has died of Aids – and gradually, we understand that everyone at the wake has slept with him.

Everyone, that is, except for Guy.

In Scene Three, all of Reg’s lovers are still alive – but now, ironically, it is Guy who has died of Aids (the result of non-consensual sex in Lanzarote with ‘a mortician from Swindon’).3 The setting remains Guy’s flat: he has left it to John. This second time-jump is even more startling than the first, and particularly heartbreaking, as Guy is so dedicated to safe sex that according to Daniel he ‘masturbates in Marigolds.’4

The fate of the play’s central figure, a self-conscious and good-natured chap inhibited by his unrequited love for John, lends the writing a deep – Chekhovian – sense of yearning and sadness.

Sex in a time of Aids

And yet at the same time, it has experienced a play that is a celebration – a celebration of gay friendship, and of gay sex. Throughout, Elyot’s characters, most of whom came of age during the heady 1970s, are brazenly sexual, wittily gay in all senses, even in the face of the new and cruel threat to their erotic lives after the liberations of their salad days. Double entendres in both the stage direction and dialogue in the fourth line of Scene One tell the audience what to expect –

GUY: (Taking it off [an apron]. I was just stiffening some egg whites.

– and this passage reflects the general tone:

They embrace again. DANIEL mauls JOHN’s backside.

DANIEL: Darling, it’s dropped!

JOHN: Fuck off!

DANIEL: Dropped, dropped, dropped! At least two inches! It’ll be dragging on the floor before the night’s out.

JOHN tweaks one of DANIEL’s nipples. DANIEL shrieks. ERIC looks on.

DANIEL: No, it hasn’t! It’s perfect! I promise!

JOHN lets go.

DANIEL: The Flying Fuck of the First Fifteen!

They embrace again.

DANIEL: Darling, be gentle! I’m still intacta.5

The sexual freedoms gay men discovered in the 1970s had been celebrated and interrogated by Elyot in his first play Coming Clean, which premiered at London’s Bush Theatre at the end of 1982, just before Aids had really made its terrible mark. In the twelve years between the two plays, a busy Elyot wrote several adaptations, and Killing Time, an original and award-winning film for the BBC. But there is a sense in his notebooks that the Aids crisis was unsettling to his playwriting: he struggled to deal with the shock of loss – the loss of lovers and friends, and the loss of sex without consequence. He was a writer interested in shame-free gay sexuality who wanted to

MAKE THEATRICAL POETRY out of casual sex, a casual pick-up.6

‘FUCK THE MORALISTS!’ he wrote,

Ruffle the feathers of the activists. Make it dead dangerous.7

For some time, he imagined Reg as a sequel to Coming Clean, with some of the same characters and arguments in that play about the gay ‘scene’ and promiscuity. Over and over in his notebooks he took the ‘non-monogamy’ position of Coming Clean’s Greg:

The thesis is that gays shouldn’t regret their lifestyle prior to Aids.

Non-monogamy – show it as a positive way of life, warts + all.

Remember, I’m not only showing gays being lustful + potentially promiscuous, but they’re being so at a wake of a guy who’s died of Aids! This is a good, exiting idea – don’t be despondent.8

A unique Aids play

Write a gay play for today – the threat of Aids and the ensuing temptation + frustration.9

But – and such dramaturgical subtlety is an improvement on Coming Clean – Aids is never mentioned by name. It hovers in the background as the interconnections between the men become clear to the audience in a paradoxically light-hearted, La Ronde-like fashion.

My Night with Reg is, then, unlike other great Aids dramas of the 1980s and early-90s such as Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: it is not agitprop against government inaction and systemic homophobia. Elyot even went so far as to claim, ‘It’s not “about Aids”. I can’t do that sort of writing.’10

It is, in Alan Sinfield’s words, an ‘unAmerican, unheroic version of AIDS – wry and understated, furtive and thwarted.’11

A serious comedy

Avoid humour, because humour seems grotesquely inappropriate to the occasion. A sniggering or wise-cracking humour puts the public (indifferent when not uneasy) on cosy terms with what is an unspeakable scandal: death. […] Humour suggests that Aids is just another calamity to befall Mother Camp.12

Since the play’s premiere, other writers have criticised it for political tameness, and anti-queerness: as every character is likely to have Aids, and the final effect is one of loss, it has been accused of being excessively pessimistic or even, as Enric Monforte argues, ‘a metaphor for the erasure of gay subjectivity’ since one by one the characters ‘disappear in a literal sense.’13

But why should My Night with Reg take White’s position concerning Aids and comedy? Why should it take the political position of Kramer or Kushner (both exhilaratingly angry in their landmark plays about heterosexual indifference or hostility towards one of the great health crises of the twentieth century)? There are different kinds of playwrights and plays, different responses to the same human predicaments. As an actor, Elyot had acted in the political theatre of Gay Sweatshop in the 1970s and early-80s, but as a playwright, he could not find meaning through agitprop:

Been there, done that. I enjoyed acting it, but I can’t write it because I find that rather simplistic. Life is too full of shades of grey. Some writers can write a state-of-the-nation piece, or a political work – I can’t. As for writing a ‘gay’ play, like say Normal Heart, I just can’t bear that sort of preachiness. Normal Heart is a terrible play.14

Elyot was a gay man who came of age in the 1970s, and he was dubious of monogamy, and Reg scrutinises what he saw as the necessity of lies in human relationships. It shows gay men who betray themselves and each other – as all human beings do – and these betrayals are dramatised in a camp, funny, knowing diction familiar to many LGBT people. Even in the face of death, the play refuses to preach. Even in the face of death, it refuses to let go of the language of gay sexual liberation that defined Elyot’s characters in the 1970s, and defined Elyot himself.

The meeting of that language with Rohmer’s moral question, in a world complicated by Aids, is authentic: to use that vapid contemporary phrase, it is a meeting forged from ‘lived experience’. ‘If you are writing well,’ Elyot argued, ‘you are touching on something that resonates with you and then it’s a truthful piece of writing.’15 He was evasive when asked whether his plays were autobiographical, but he defended himself to Gay Times:

One of the starting points for writing Reg was personal experience. I’ve suffered in similar ways to other gay men of my generation, experienced the same grief, loss and trauma.16

Ultimately, Elyot’s position in Reg (and other plays) is a tragicomic position true to himself – and that position is, in any case, Shakespearean. In the words of Alan Hollinghurst,

Elyot himself has gone, but his plays survive, to haunt, to disconcert and, in a favourite line of his from Love’s Labour’s Lost, ‘To move wild laughter in the throat of death.’17

Sometimes, Reg argues, the tragedy of Aids – the pain of any tragedy – can be conveyed by the ways people emerge from their grief, loss and trauma, or fight them, with camp, with wit, with double entendre.

Inexpressible loss

For many words about Aids, important words, we have plays by Kramer and Kushner. For the sense of the inexpressibility of loss in the time of Aids, we have the plays of Elyot; and in the end, I most admire his writing for the same reason as the journalist David Benedict:

The distinguishing mark […] is his rare confidence in leaving things unsaid, allowing the actors to finish the thoughts.18

In My Night with Reg’s final scene, there’s a wonderful example.

Guy is dead, and Daniel has visited John in what is now John’s flat. It is early morning and the birds are singing. Eric, the play’s archetypal gay youth, is in the kitchen making coffee. We know that both Daniel and John have slept with Reg. John has not admitted to his friend his betrayal. We also know – somehow we just know – that both men are likely to have contracted HIV, and that in the play’s unseen Scenes Four, Five, Six, the wakes will continue. The stage direction says the men ‘kiss affectionately,’ then:

DANIEL: I think I’ll go. I’m suddenly very tired. Apologise to Eric, will you?

JOHN: Yes.

DANIEL goes to the door.

JOHN: Dan?

DANIEL stops and turns. They look at each other. A couple of other birds have joined in the singing.

DANIEL: Yes?

Beat.

JOHN: I’m pretty tired, too. I haven’t been sleeping too well lately.

Beat.

DANIEL: We’ll speak later.19

I will never forget this moment in Roger Michell’s original production. I remember it particularly because of John’s line, ‘I’m pretty tired, too,’ which from the actor Anthony Calf was, to my ears, a primal scream, ringing with subtext:

I want to be honest with you, my dear old friend, honest with you about my betrayal of you with Reg – but I also want to tell you that I think my body is being attacked, that the physical in fact leads to sickness, that my exhaustion tells me I’m dying, are you dying too, what happened to our glorious youth, Dan, help me please, my dear old friend, poor Guy, what are we all going to do?

It takes courage to write like this – to keep so much unsaid – even though such dialogue holds a mirror to the games of intimation, elusion, allusion and self-delusion that human beings play every single day of our lives.

Anyone interested in playwriting, or how plays reflect life, should study the passage: it’s a superlative example of less is more, of showing not telling, of Elyot’s great talent at compassionately and truthfully depicting flawed human beings trying to come to terms with things outside of their control.

This work was inspired and developed through the generous support of the Kevin Elyot Award at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection.