Over the past six months, a generous private donation has made possible the cataloguing of BTC30: The Irving Family papers. Donated in 2006, with a recent addition of papers kindly donated by the family of Sir Henry Irving’s grand-daughter, Lady Elizabeth Brunner, this collection spans four generations and 140 years of the legendary Irving family and documents their place in theatre history. Through the collection we gain an insight into the business of theatre, the minutiae of running a theatre, designing for theatre and film and researching theatre history. At the same time, we witness the transition of theatre from risqué demi-monde to cultural powerhouse, capable of catapulting its exponents to stardom with the right role and even the birth of film as a medium. We also get a glimpse of the people behind the celebrity and witness the breakdown of marriages, the grief over the early death of a son and the struggles of subsequent generations to reconcile themselves to the long shadows cast by their most famous forebear.

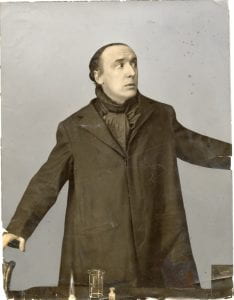

The figure of Sir Henry Irving arguably marks the apogee of the rise of the great actor-manager, becoming the first actor to be knighted for his theatrical work. His papers in the Irving Family Collection mainly deal with the minutiae of making theatre, comprising legal agreements over the rights and commissioning of pieces and Lord Chamberlain’s licenses for the performance of specific plays as well as theatre licenses and wines and spirit sale licenses (BTC30/2/2/1). And yet amongst these seemingly mundane papers there are glimpses into Victorian popular culture at its height. An agreement over the transfer of rights to the music for a production of Macbeth in 1888 (BTC30/2/1/31) directly connects three legends of Victorian popular culture. The composer for this production was Arthur Sullivan, most famous of course for his operatic collaborations with W.S. Gilbert, and the role of Lady Macbeth was played by Ellen Terry, Henry Irving’s leading lady from 1878 to 1902 and one of the most famous actresses of the age. So electrifying was her performance on the opening night, that John Singer Sargent allegedly left the theatre and immediately began work on a portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, which now hangs in the Tate (‘Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth‘, John Singer Sargent, 1889 | Tate). And so, this one agreement brings together composer, actress and artist, uniting the worlds of music, theatre and art in one single document.

The collection also reveals the darker side of Sir Henry’s acting celebrity. Although he reached, arguably, the height of Victorian society, Sir Henry’s decision to pursue an acting career caused an irretrievable breakdown in his marriage. Although we might consider that the conservative Victorians disapproved of divorce, BTC30/3/2/1 reveals the ways that the Irvings negotiated this disapproval, organising a formal separation which covered Florence Irving’s maintenance, the custody, schooling and visitation of their children and even Florence’s concern that Sir Henry’s friendship with another woman would, despite their separation, reflect on her.

The collection reveals the long shadow that Sir Henry Irving cast, and the very different ways that his descendants chose to forge their own paths. Sir Henry’s elder son Henry Brodribb Irving began acting in student productions for the Oxford University Dramatic Society before beginning, despite his father’s reservations, his own acting career. Henry tried to forge a separate path from his famous father, although on a parallel track; founding his own acting troupe, which toured South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, before taking over the lease of the Savoy Theatre and following his father’s lead as actor manager. He also reprised some of his father’s productions, including The Lyons Mail and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (although he used a new dramatic adaptation by J. Comyns Carr, rather than the infamous Richard Mansfield version that his father had brought to the Lyceum in 1888).

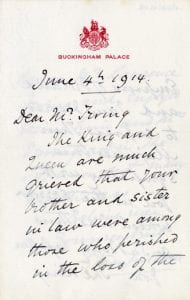

His brother Laurence Sydney Irving, on the other hand, worked directly with their father, acting with Sir Henry Irving’s troupe for several years. However, Laurence forged his own path as a writer, with several of his plays performed by Sir Henry’s Lyceum troupe before he went on to found his own acting troupe, taking it on tour in the USA and Canda. It is unclear to what extent Laurence Sydney Irving would step out from his father’s shadow since both Laurence and his wife would perish in the sinking of the Empress of Ireland steamship, sunk as it left harbour in Canada, in June 1914 with the loss of up to 1000 lives, including that of the young Irvings.

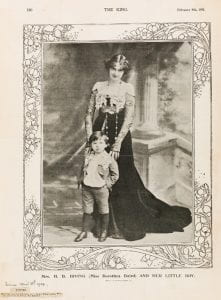

The collection also reveals the rise of the celebrity actress. Perhaps learning from the breakdown of their parents’ marriage, both Henry Brodribb and Laurence Sydney Irving married fellow actors. In the case of Henry Brodribb Irving, his wife Dorothea had already begun to carve out her own theatrical career and her part of the collection reveals some of the difficulties faced by actresses in the era, the potential for them to reach meteoric success and even the difficulties of being too closely associated with one role. BTC30/6/3/2 are transcripts of letters exchanged between Dorothea Baird, her future husband and other members of her family describing the trials of life on tour, including the difficult line walked by actresses who wished to retain their so-called moral character. The letters also reveal Dorothea’s attempts to provide her own costumes as well as her enthusiasm for the new hobby of cycling. However, this enthusiasm had its downside when Herbert Beerbohm Tree had to provide Dorothea with specific makeup since her relentless cycling had made her altogether too healthy for her to be a convincing corpse in the final act of Trilby!

By the third generation, the Irving family’s theatrical talents had developed in other directions, although Henry Brodribb and Dorothea Irving’s daughter Dorothea Elizabeth (Lady Elizabeth Brunner) had a brief acting career before turning her attention to charitable activities, becoming Chairman of the National Federation of Women’s Institutions, organising the building of the Women’s Institute training centre Denman College and founding the Keep Britain Tidy Campaign. Her brother, Laurence Henry Irving also kept the theatrical flame alive, albeit as a designer and theatre historian rather than as an actor himself.

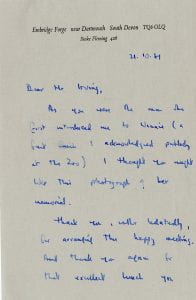

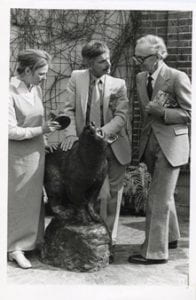

After a wartime stint as a pilot in the Royal Naval Air Service during the First World War (during which he was awarded the Croix du Guerre), Laurence Henry Irving enrolled at the Byam Shaw Art School and then the Royal Academy School, hoping to begin an art career, and in the 1920s he illustrated two books. A fortuitous introduction in 1926 set him on a theatrical path, and incidentally, led to the creation of one of children’s literature’s most enduring, and endearing, characters. In 1926, Laurence Irving was invited to design the sets for two numbers in the musical revue Vaudeville Vanities, and he struck up a friendship with the writer of one of the numbers, one A.A. Milne. As both men had young families of about the same age, Laurence Irving organised a trip for their children to London Zoo, the highlight of which was to be a feeding of Winnie, a Canadian Black bear, who had been brought to the UK as a regimental mascot for a Canadian regiment during the First World War, and who had remained in the care of London Zoo after the war. Milne’s young son Christopher, after some initial reservations, became fascinated by Winnie and this interaction inspired Milne to create his fictional bear, Winnie-the-Pooh. But without Laurence Irving’s involvement with Vaudeville Vanities, Christopher Robin would never had met Winnie the bear, and thousands of children’s lives would have been immeasurably poorer!

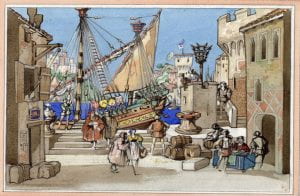

Laurence Henry Irving continued to be closely associated with the theatre, designing sets and costumes for numerous productions including Punchinello at the Globe, Becket (the play in which his grandfather made his last ever appearance on the night he died) and even Hamlet for the Old Vic. In 1929, silent film star Douglas Fairbanks invited Laurence Irving to California and he began a career as a film designer, designing for two Douglas Fairbanks films; The Taming of the Shrew and The Man in the Iron Mask. Returning to Britain in the 1930s, Laurence Henry Irving continued to design for several British films, most notably Moonlight Sonata, starring Polish statesman turned concert pianist Jan Paderewski, and Gabriel Pascal’s adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. The latter allowed Laurence to finally call a halt to an acrimonious dispute with George Bernard Shaw which had begun two generations earlier with Shaw’s disparaging comments on Sir Henry Irving’s funeral.

The collection also reveals the deeper impacts Laurence Henry Irving had on the development of twentieth century theatre. In 1933, shortly before he returned to Hollywood to design Douglas Fairbanks’ film version of The Man in the Iron Mask, Laurence Irving had become involved in the Canterbury Festival of Music and Drama, which commissioned as its first annual play The Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot, beginning what some consider the revival of religious drama, and Irving remained involved with the Canterbury Festival for decades. He was also a board member of RADA, continuing three generations of Irving involvement in the school; following on from Sir Henry Irving’s role as a trustee of the school and Henry Brodribb Irving’s donation to the school of a portion of the proceeds from his starring in an early film.

Laurence Henry Irving, and later his son John, also carved out their own place in the Irving family as historians and researchers. In 1959, Laurence Irving published “Sir Henry Irving; the Actor and his World”, a biography of his grandfather, following it up with “The Successors” in 1968, the first of a proposed trilogy of books covering a century of theatre history as seen through his own family history. John Irving, Laurence’s son, while continuing his own career in television and radio (and one of John’s letters to his father is particularly interesting for its descriptions of the preparations in his BBC department for the arrival of television) continued his father’s interest in their family history. In 2006, John oversaw the publication a section of his father’s autobiography dealing with his time in Hollywood as “Designing for the Movies” (BTC30/10/1) and he was also an influential figure in the Irving Society, conducting research on and bringing together copies of many of the collections of Irving material held in overseas collections, including Harvard University, San Marino California and the papers of Stephen Coleridge, as well as conducting family research on the Brodribb family, into which Sir Henry Irving had been born, having changed his name from John Henry Irving Brodribb when he began his stage career.

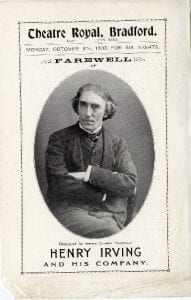

As well as the professional lives of Irving family, the collection also allows us glimpses into the private lives of these celebrated theatrical figures. BTC30/2/1/53 is especially poignant. At first glance a routine programme for a regular touring performance of Henry Irving and his company in Becket and The Merchant of Venice, a closer examination of the date reveals that the last performance of The Merchant of Venice advertised, never took place as Sir Henry Irving died on the evening of 13 October 1905, after the evening performance of Becket, truly a farewell performance.

Only a decade after Sir Henry Irving’s relatively early death, Florence Irving would lose both her sons within five years. Laurence Sydney Irving died in 1914 when the steamship Empress of Ireland on which he was travelling was sunk in harbour in Canada, inciting a flood of condolence correspondence to his mother and brother. Then in 1918, Henry Brodribb Irving died of a kidney disease at the age of only 49, leaving his mother, his wife and his two children. Celebrity is no defence against grief, and despite their legendary reputation, the Irving Family collection reveals both the public commiserations and the very private griefs.

These are just a very few of the many stories that have been revealed during the cataloguing of the Irving family papers and we are expecting a new addition to this collection that will hopefully reveal many more. Or you can search for some of these stories yourself. The Theatre collection is open to researchers from Tuesdays to Fridays and we welcome visitors and researchers alike. Or you can consult our online catalogue (Theatre Collection (calmview.co.uk)) or our website (www.bristol.ac.uk/theatre-collection) for more details.