As part of the Wellcome Trust funded project Challenging Archives: Delivering research access, public engagement and the curatorial care of the Franko B archive, writers-in-residence Mary Paterson and Maddy Costa are engaging creatively with the Franko B archive as it is catalogued, conserved and made accessible. Their blog posts reflect on the complex set of challenges the Franko B archive poses, the archival process and Franko B’s artistic practice, which explores issues such as the limits of the body and the human condition, dealing with pain, suffering, abuse of power, empathy, eroticism, and sexuality in contemporary culture.

This post was inspired by a visit to Textile Conservation Ltd, a private studio in Bristol overseen by Alison Lister. It is mostly written by Maddy Costa, but with texts by Mary Paterson stitched into its fabric, a nod to the spirit and collaborative ethos of Lister’s work. Mary’s texts are from our publication Challenging Archives, which is being printed in a small run of 500, and will be available from 6 March 2020. In repurposing Mary’s words, it is possible that I’ve shifted them from her original meaning, misinterpreted or cut them into new shapes.

Together Mary and I will be looking further at how Franko’s archive can be a a tool for creative research and inspiration, at a workshop in Bristol on the evening of Tuesday 10 March 2020. Further details, including the booking link, can be found here.

1

the blood keeps moving

It’s not often that textile conservator Alison Lister is asked to preserve blood. “Unless,” she says, with a shadow of a smile, “it’s needed for evidentiary purposes.”

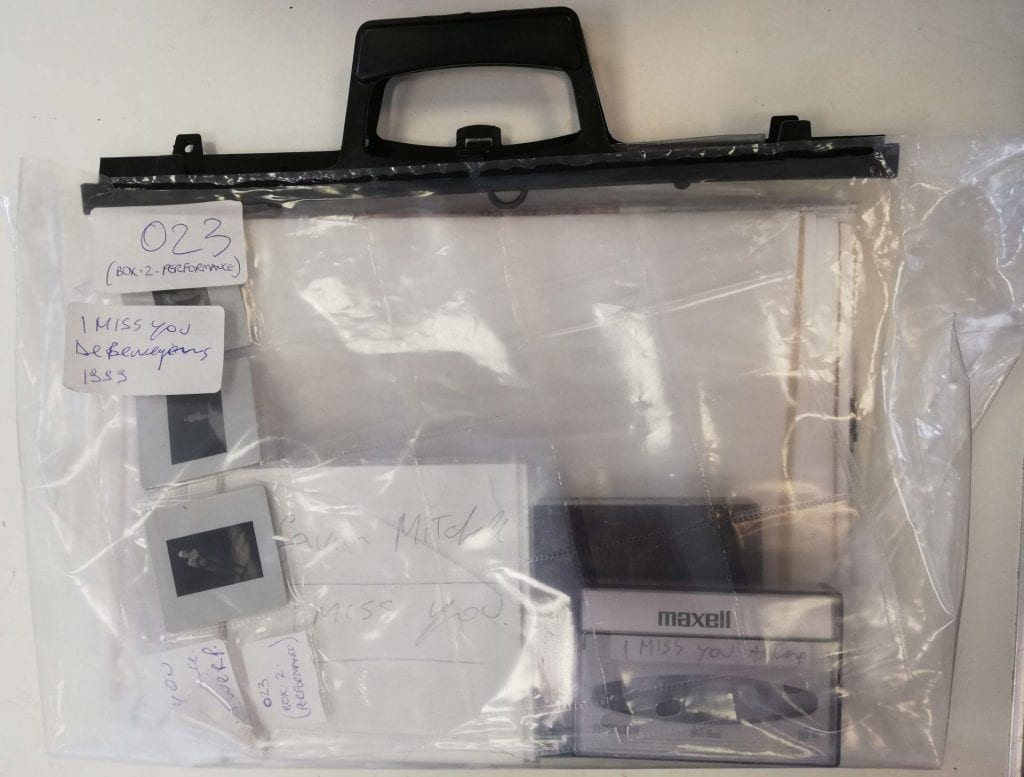

The blood on the piece of canvas Lister stands beside as she says this is evidence of a kind. It was shed by Franko B during a performance of I Miss You (1999-2005), and it is – in Lister’s words – “actively to be kept”. This is difficult, because the blood itself keeps active. Already it is a different colour from what it was five or ten years ago, dried to a deep, deoxygenated brown, so dark it’s almost black. And the chemical processes of the blood are still ongoing. Blood is moving in the canvas right now, dissolving its threads, eating its innards. “Eventually,” says Lister, crisp in a pristine white lab coat, “the blood will work its way through the material completely.”

How long that will take, she adds, is impossible to say.

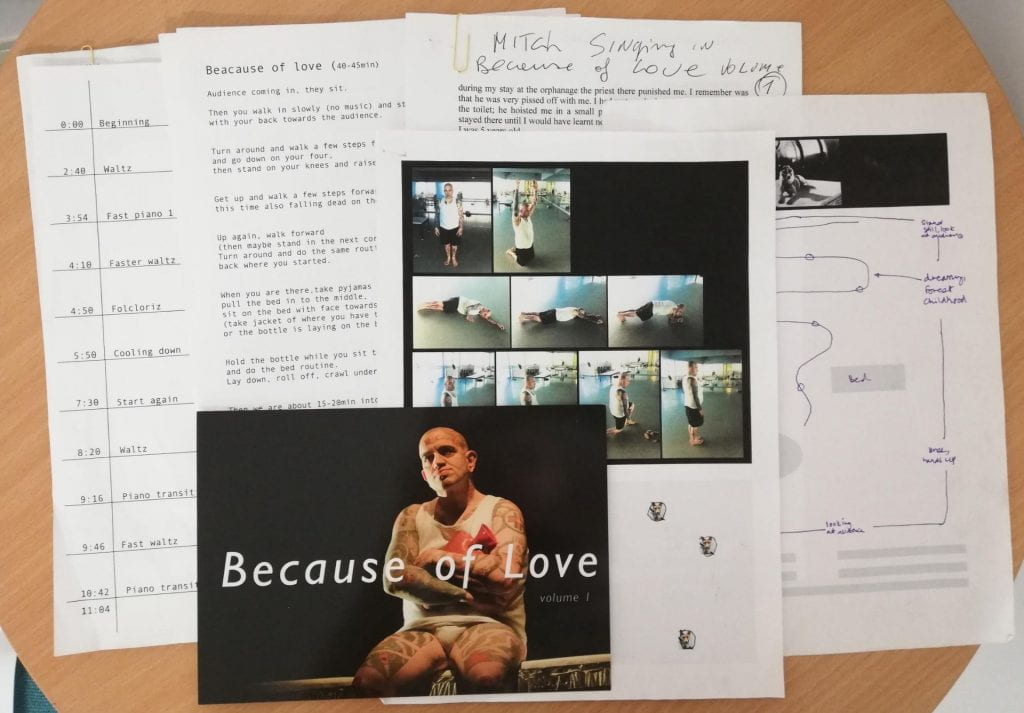

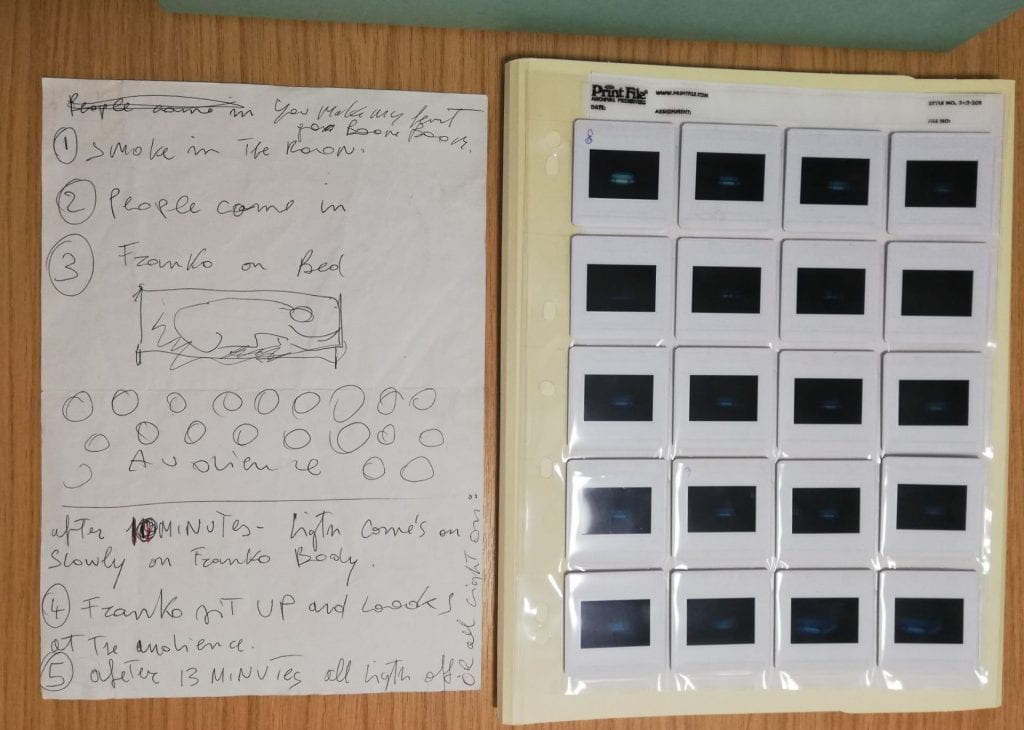

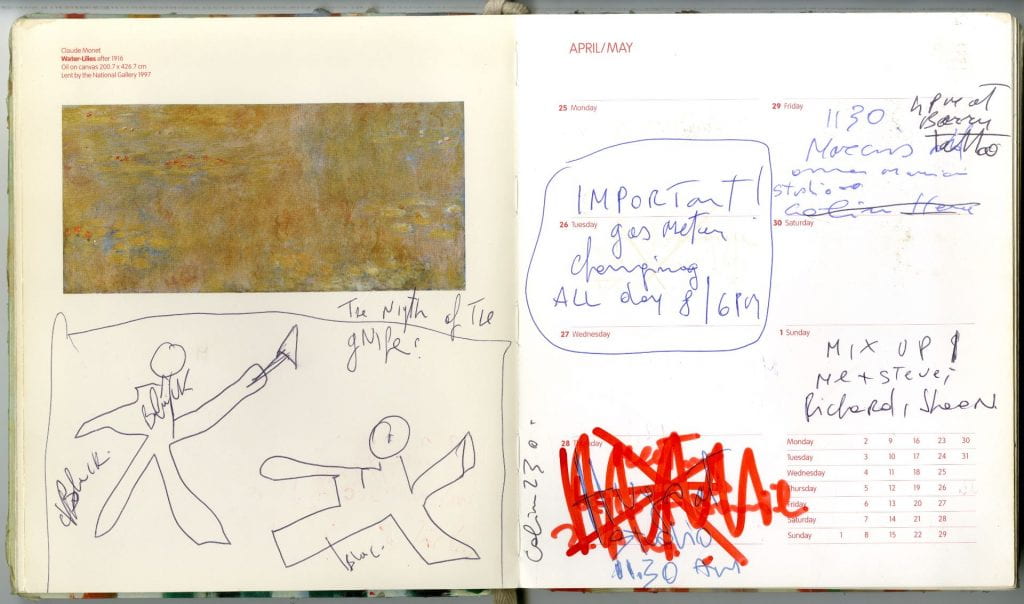

I Miss You is, perhaps, Franko B’s most iconic work. During ten performances over six years, the artist covered his body with white paint and covered a long strip of floor with white canvas. He walked up and down the canvas, like a model at a catwalk show. The audience was packed in tightly on either side. One vein on each of Franko B’s arms was sliced with a small blade, and he was bleeding. Mary, who wrote those words, never saw one of these performances, but has held Franko’s body in another of his works, felt the sweaty exhaustion of it watching Milk & Blood, and has a mental image of I Miss You that begins to feel like memory. Maddy, who wrote these words, has a different set of memories: of school holidays spent in the clothing factories where her parents worked, cutting, sewing, pressing, trimming loose threads from each garment, soon learning enough to set up a factory of their own. These differences follow us through the doors of Lister’s studio, on the outskirts of Bristol, and condition how we experience her work, what we notice, what we remember.

After performances of I Miss You, Franko B gave the canvas catwalks to designers and asked them to fashion a wearable garment, according to their own taste and whims. For Julian Warren, archivist at the Theatre Collection at the University of Bristol, these are now art works in their own right: not remains of the moment, but beyond the moment. Among the items stretched out on a table in Lister’s studio are a T-shaped jacket or tabard, and a long flared kilt; items boxed and awaiting attention included a heavy hooded jacket and a pair of stumpy platform boots. Lister’s task is to preserve them for the archive: which in this case means accepting one kind of deterioration while preventing another. She speaks of packing each garment “in a way that it’s not a danger to itself – for instance, not having the metal elements touching anything”, and ideally as flat as possible, padding any folds into a soft curve, because a sharp crease would wear into a tear over time.

She also needs to “avoid blood crossing to other bits of fabric”, a phrase that connotes a fear of contamination – startling, given that the fear of contamination that Franko challenges and decries with his bleeding works, the fear of gay men and blood potentially contaminated by Aids. Blood corrodes – but once it’s dried it’s not a health hazard, says Lister. The only danger here, the one Lister is taking such care to avoid, is to Franko’s legacy, to possible future encounters with his work.

The blood keeps moving. Its existence is mutable. It is part of the choreography of time.

2

textiles are intimate with bodies / made to be laid next to the skin, draped across your shoulders, held close for comfort / warmth / identity

Lister’s studio is bright, almost oppressively so, overhead strip lighting bearing down on a motley array of intricate fabric pieces, each an emblem of a bigger story. But the room is also serene: classical music whispers in the background, and when a textile item is not being worked on it is protected beneath a drape of snow-white sheets. There are four workspaces: pieces from Franko B’s archive occupy one; at another, Lister’s assistant is tending to a pair of Napoleonic epaulettes; opposite her is a handkerchief hand-embroidered by a first world war solider; to her left stands a dress model wearing the costume that adorned artist Andrew Logan at the first ever Alternative Miss World, its two halves – one conventionally masculine, a suit; the other conventionally feminine, all lace and flounce – temporarily unstitched and waiting to be reunited. At the next workstation there’s a huge tapestry from a National Trust property, most of it rolled up – opened out, it would dominate the room. Lister stands beside the final table and draws back its layers of sheeting, to reveal – another startling moment – a T-shaped tabard of uncannily similar design and dimensions as Franko B’s. Only this one is made of feathery silk, stitched in the early 1800s for the first Duke of Wellington.

Where Franko’s garment is robust, stern, stiff, the Duke’s is terrifyingly fragile. Its painted gossamer silk has fractured into jigsaw pieces; Lister’s task is to restabilise them into a single entity, to be returned to public display. I find I can’t look at it, that looking at it induces a mild panic attack. My fingers prickle at a memory: of taking down a set of curtains I’d made myself, for my bedroom 18 years ago, from a stiff organza silk. Four years of exposure to sunlight had damaged the fabric irreparably; as I took the curtains down they crumbled in my hands, into skin cells, into dust.

These textiles were made to be laid next to the skin, held close for comfort. The fabric asks to be cared for. It asks for care.

3

her wrists arc over the fabric / her neck bends over the fabric / her body follows the original weavers’ movements / like an embrace

When she works on the tapestry, Lister leans in close, tracing the original stitches with her own. Each mark she makes in the act of repair is sewn onto a secondary backing. She is writing a crib sheet for questions, expected but as yet unknown. Every new stitch must be accounted for, identifiable as such, as a modern intervention. There is a difference, Lister says, between preventive fabric conservation – the measures taken to avoid decay before a textile work is even made – and interventive. As a private practitioner, intervention is where her focus lies.

The word conveys a violence far removed from the close caress of Lister’s fingers. Once, she says, she found a centuries-old human hair woven into the back of a carpet. There is a human tactility to fabrics: they were made by people, worn by people, and those people are here with you.

4

S/he lifts the object with gloved hands. S/he places the object in a box the shade of dove grey. S/he releases the object to a bed of tissue paper. It makes a sound like fresh snow.

I’ve heard Franko B describe himself as an image maker, rather than a performance maker. But his images are sewn into the fabric of time. Their mortality is part of their language. That’s what makes them so human. Mary, who wrote those words, looks at Franko’s textile pieces and warms at a memory. Franko B’s work is vulnerable, she writes: here is a man, naked and hurting, and here are you. Here are you. And here is another human being. And here are you. There is no room for gaps, for endings; there is no end to this work: it is a practice of being alive. It is a practice of being interconnected, of needing more than anyone can ever give, of giving more than anyone can ever pay for, of stretching beyond the limits of your own body into the sinews of other people’s minds.

This is not quite what I see when I look at Franko’s textile pieces.

Mary and I, accompanied by Julian Warren and his colleague Sian Williams, return with Lister to the Franko table. I lean in close to examine the stitches on the kilt. The fabric is thick, heavy, rough beneath fingers; I know because I’ve stitched fabric like this myself before, felt its weight drag against the needle, as though refusing to be manipulated. Sure enough, the stitching of the kilt is wayward, wobbly; I can see the hands of the person attempting to sew it, struggling to control the material as they fed it through the machine, unable to produce a truly straight seam. I realise that as remains of the moment of performance, an iconic performance by Franko B, the canvas itself is so monolithic that I feel little connection with the man, naked and hurting. Instead it is an object beyond the moment, and becomes alive to me differently, as a record of the vulnerability of another human being. I see that vulnerability in every stitch, and it’s unexpectedly visceral to witness.

The liveness continues, says Lister. She demonstrates how Franko’s fabric pieces will be packed, so that the “most interesting aspect is immediately visible”, to minimise the need for unpacking. The protective fabric sheeting of her studio will be replaced by protective sheets of tissue paper, interleaved between every delicate fold. There might be dirt ingrained in the fabric but that too was of the moment. From now on it will be the responsibility of every visitor to the archive not to damage it further with their touch.