As part of the Wellcome Trust funded project Challenging Archives: Delivering research access, public engagement and the curatorial care of the Franko B archive, writers-in-residence Mary Paterson and Maddy Costa are engaging creatively with the Franko B archive as it is catalogued, conserved and made accessible. This is the third in a series of blog posts that will reflect on the complex set of challenges the Franko B archive poses, the archival process and Franko B’s artistic practice which explores issues such as the limits of the body and the human condition, dealing with pain, suffering, abuse of power, empathy, eroticism, and sexuality in contemporary culture.

This post responds to the second blog post, published here.

In Response to Maddy, Katrina, Ash

by Mary Paterson

*

Mary, I’m curious where this overlaps with or differs from your own experience, as someone who studied the history of art. What do you still apply from that study, in terms of approaches, questions, principles or practices? What have you since rejected or found to be unhelpful?

Shortly after I left university with a degree in Art History, I started working as a receptionist in an artists’ studio organisation. The university where I had studied presented Picasso as the most modern of modern artists, and the sole module offered on him was oversubscribed. So I studied historic periods: principally, the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. All of which is to say, it was a shock to meet an actual artist. And even more of a shock to realise artists had real opinions.

Just like Katrina, my studies had focused on the interpretation of the work of art as an object. In this scenario, the art object takes on the status of something like a natural phenomenon – as still and steady as a rock formation. This type of study, of course, is frequently concerned with art objects so famous they really do constitute a naturalised cultural landscape: the great cliffs of Rubens, Rembrandt, Renoir …

Later, I pursued a Master’s in Visual Cultures: an offshoot of Art History, inspired by the politics of civil rights in the 1960s and 1970s. Taking an anthropological model instead of an historical model as its basis, Visual Cultures promised to consider the stories that traditional histories have hidden from view. In this scenario, the art object is less like a rock formation than a fossilized skeleton dug up from the earth. Art is a record of its context, both a crystallised impression of a specific moment, and a clue to the environment at large.

Visual Cultures shifts the focus from art as object to art as relationship, but my studies still mined a distance between the art work and its affect. Inside this distance, in both my degrees, sat the art historian: investigating, interpreting, informing. This is the position I have tried to avoid being in, ever since, although I’m not sure if it’s a position sculpted by the disciplines, or by the learning environments of schools and universities – which instrumentalise the discoveries of meaning.

Just as you describe, what has always been so captivating to me about Live Art is that it collapses the borders between agents, subjects and objects, creating an avalanche of meaning that makes this distance impossible to preserve. Watching Live Art – particularly body based Live Art – I feel connected to the artist, who is the art, which is the audience, which is the affect, which is the meeting, which is the art.

Maddy: you studied English at University. I tried to do that too, but had to give up because I couldn’t bear to read (or write) turgid pieces of literary criticism instead of beautiful works of literature. In literature, the art object takes a different form: rarely a single item, the text is mass produced in different versions; although the power struggles between artist and critic remain the same. What does the study of literature have to teach us about how to approach the archives of Live Art?

*

Mary, one of my favourite stories you’ve told me of your life before I knew you is of being a student in Edinburgh and discovering feminist performance art in the archive. Is this something you went looking for? Or something that found you?

I didn’t discover feminist performance art in Edinburgh (where I did my first degree), but at Middlesex (where I did my Master’s). Getting to grips with the discipline of Visual Cultures, and armed with the relatively recent discovery that artists are people, I began to explore the visual, social and psychological landscapes of art within living memory. I was looking at artists from the 80s, the 70s, the 60s, the 50s. I went backwards like that – from things I could recognise to the things those things were referencing, and so on. I rewound through the library shelves, from colour to black and white, from VHS tapes to still images, from pictures to descriptions of acts nobody had planned to remember.

I remember the thrill of watching a grainy film of Hannah Wilke from the 1970s. In the film, she is stripping off and making ridiculous shapes in front of Duchamp’s The Large Glass. Her body and her attitude are a challenge to the male gaze and the cult of the male artist. Her later photographs document the disintegration of her body during cancer and its treatment. Now her long limbs and smooth skin are bloated and yellow. She stares out of the pictures, eyes fixed on mine. She is echoing a pose from years earlier, in which those same eyes gazed from a field of tiny chewing gum sculptures – models of vulvas, dotted all over her face.

Like many women, I had always hated my body for the way it mediated other people’s opinions of me. Now, I was discovering this archive of feminist performance art – often labelled ‘explicit’ – that imagined an entirely new relationship between a body and a (gendered) self. I don’t know whether I found the archive or it found me, but I do know that I was in desperate need of a new landscape to live in. My memories of this time are visceral, as if my body was really encountering these artists’ bodies. I think of this physicality as a quality of the work, which refuses to be an object; and as a quality of the archive, which requires the touch of your hand on the page, the weight of your finger on a button, the intimacy of your breath.

Is this the difference between the performance of the academy and the performance of the archive? The academy requires its students (and, increasingly, its teachers) to show their workings as they trample over familiar ground. The archive requires nothing but your attention. It predicts nothing but your time. What happens in the archive? What secrets does it hold?

Recently, I saw some of Wilke’s vulva sculptures exhibited at a show of women artists at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. They were lined up in a vitrine, like specimens in a museum. I leant close to the glass. The closer I got, the more the glass began to mist. The sculptures began to fade from view, so I shut my eyes to remember them. I imagined Wilke’s wet saliva still glistening in their folds.

Maddy: what is the cultural landscape that Franko’s archive imagines? What is it for you?

Mary, around your creative practice you also work as a producer, in finance, on the board of a National Portfolio Organisation: that is, you do a lot of the invisible work that goes into making performance happen. I’m interested in two things here: the ways in which a neoliberal culture deploys invisibility, often to make invisible both the workings of its own power and the machineries of inequality; and also the invisibility of care that makes capitalism possible, whether it’s care for children or those who are too old or too sick to be part of the capitalist machine. You and I have talked about the feminisation of care, and how that is integral to its eradication from view within a patriarchal culture. I’m curious how we can make all this visible in our project, as writers-in-residence with Franko’s archive, how we can question these absences – but also how we can make sure we see them, given their absence, their seeming invisibility.

There are two ways in which care becomes diminished in our society. One is the way in which it is rendered invisible by capitalism – a system based on the exploitation of labour for financial value, which cannot (as a matter of survival) recognise the affects and effects of non-financialised care. The other is the way in which it is rendered visible by capitalism – a system based on the promise of economic potential, which speaks only in relation to how this potential is lost or gained.

This is why caring for people has such low status: the very act of care implies the economic potential of both carer and cared for is curtailed. It is also why it never works to talk about care in capitalist terms – to describe the economic ‘cost’ of care work, for example; to do so is to diminish the topic of ‘care’ to ‘capitalism’, which is both smaller than care and ignorant of its meanings.

I could replace the word ‘care’ in the sentence above with ‘art’ and it would still ring true. I could replace ‘care’ with ‘grief’, or ‘social relations’, or ‘mental health.’ And yet, we still care for each other and make art, grieve and have relationships. We do these things and we talk about them. And that, I think, is a testament to the fact that although we are disciplined by it we are not enslaved by capitalism: its values are not our values, its terms are not our terms, its limits do not approach the richness of our lives.

The objects in an archive will degrade. Their financial depreciation is as sure as your next breath. Are these the kinds of secrets that lie in wait inside?

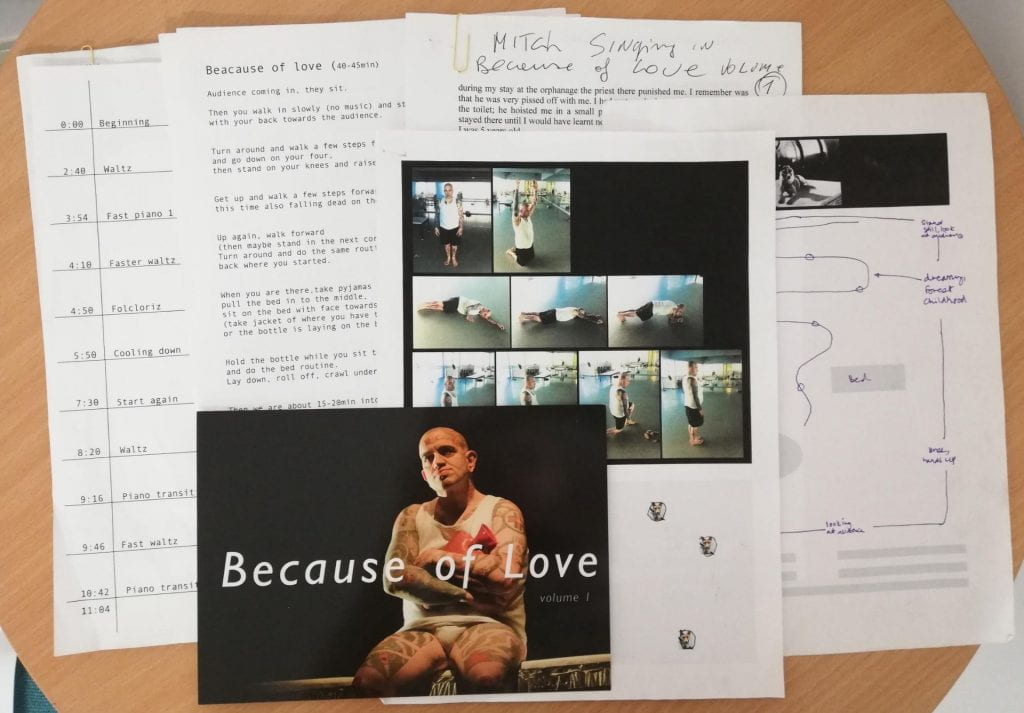

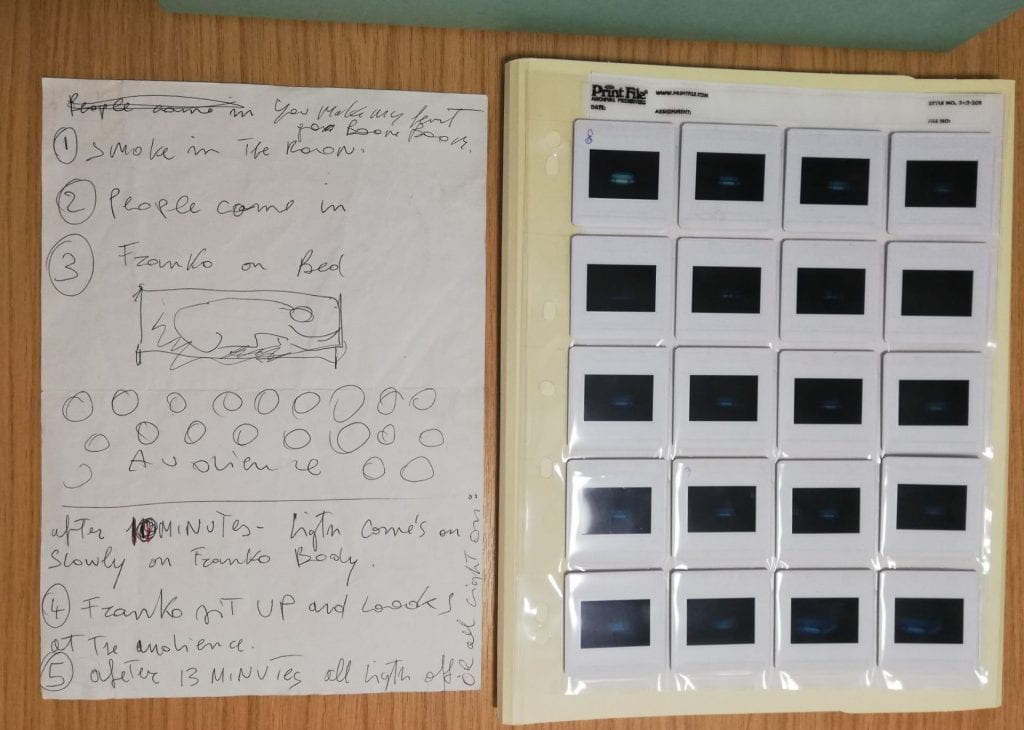

I know the buzz of finding administrative detail in an archive. Looking through the Edge 88 archives, for example, is to find (amongst other things) a series of fruitful glimpses of the planning process: funding procedures, letters of invitation, suggestions of space required to put on a performance art festival in a run down part of London in the 1980s. Reading about artists’ ambitions for screen sizes or room layouts is an important way to bust the myth of the all knowing artist-genius, as well as the myth of the always perfect art-object. It anchors the work of art to artists’ intentions, and simultaneously destablises those intentions with their clumsy corollaries: mistakes, coincidence, luck. This administrative care work roots art in the networks and complexities of life.

But I wonder if looking for evidence of this kind of activity – the desire to render this care work visible – is also a way of asserting the power of interpretation: the art historian as the arbiter of truth, and the judge of what should be remembered. What if we start from another perspective: that care is held in these boxes of photographs and flyers in the Franko B archive, and in the intention to keep them? What if we remember how this archive came about: as a personal collection gifted by the artist to an institution? What if we think of this collection as a practice of care, which is not represented or contained by any of its individual objects, but sustained in the ongoing encounters they have with curators, researchers, visitors, and our collective imaginations?

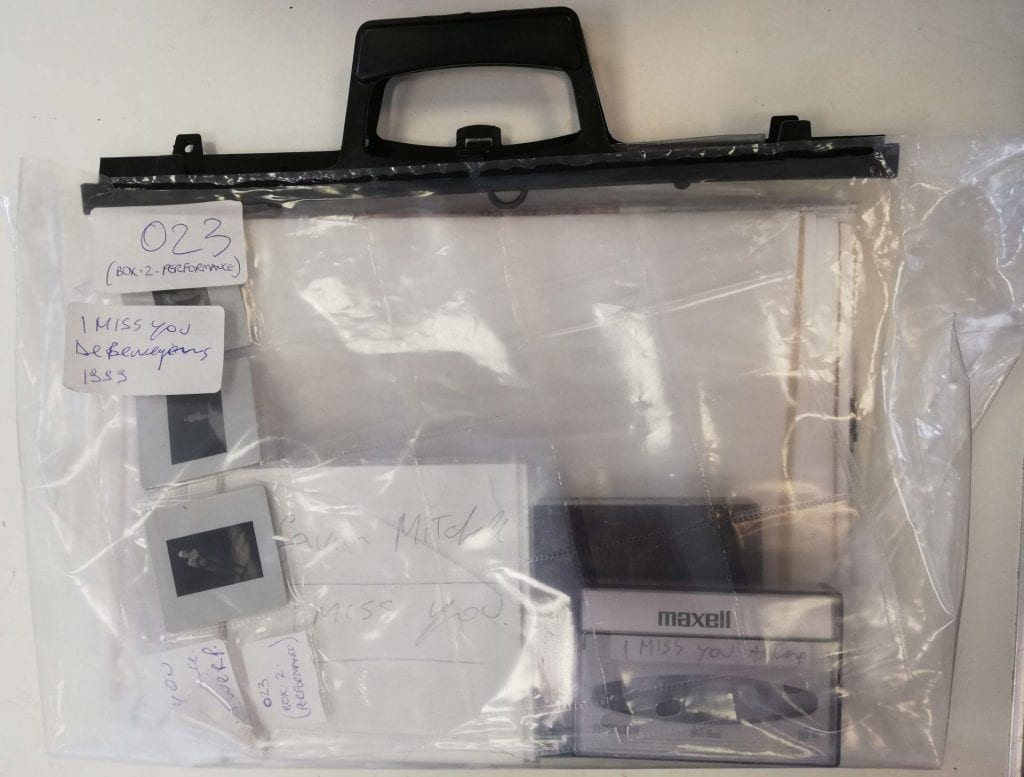

In other words: what if we think of Franko’s archive as a complex and multi-layered series of acts of care? It was an act of care to keep this material (do you still have a copy of your undergraduate dissertation?), and then to give it away. It is an act of care from the archivists to take this material, to consider its preservation, and to make it available. None of the relationships involved in this network of care is transactional, in the sense that none of them is complete: Franko has not stopped collecting, the archivists will not stop preserving, the archive will not stop being ready for visitors. And, waiting for the visitor’s touch, none of the objects is complete, either.

In a transaction, one thing transforms (or pretends to) into the next – labour into money; or perhaps, the moment into the document, the present into the past. But in a relationship of care, something remains. Your life is always worth more than the things you do with it. Your memories are never sealed in collections of words. Time does not sit quietly in the past, but persists in the movement of your body, curling its ideas into the tension of your spine.

All these things are clear to the people who care for you.

I think this is what people mean when they talk about the ‘explicit’ body in performance. It is not the material of the body that’s explicit, but the expansive and unknowable landscape of its relations to other people. As Franko often says, his work isn’t shocking. War is shocking. Famine is shocking. Exploitative and degrading capitalism is shocking. Instead, I think of Franko’s work as vulnerable: here is a man, naked and hurting, and here are you. Here are you. And here is another human being. And here are you. There is no room for gaps, for endings; there is no end to this work. It is a practice of being alive. It is a practice of being interconnected, of needing more than anyone can ever give, of giving more than anyone can ever pay for, of stretching beyond the limits of your own body into the sinews of other people’s minds.

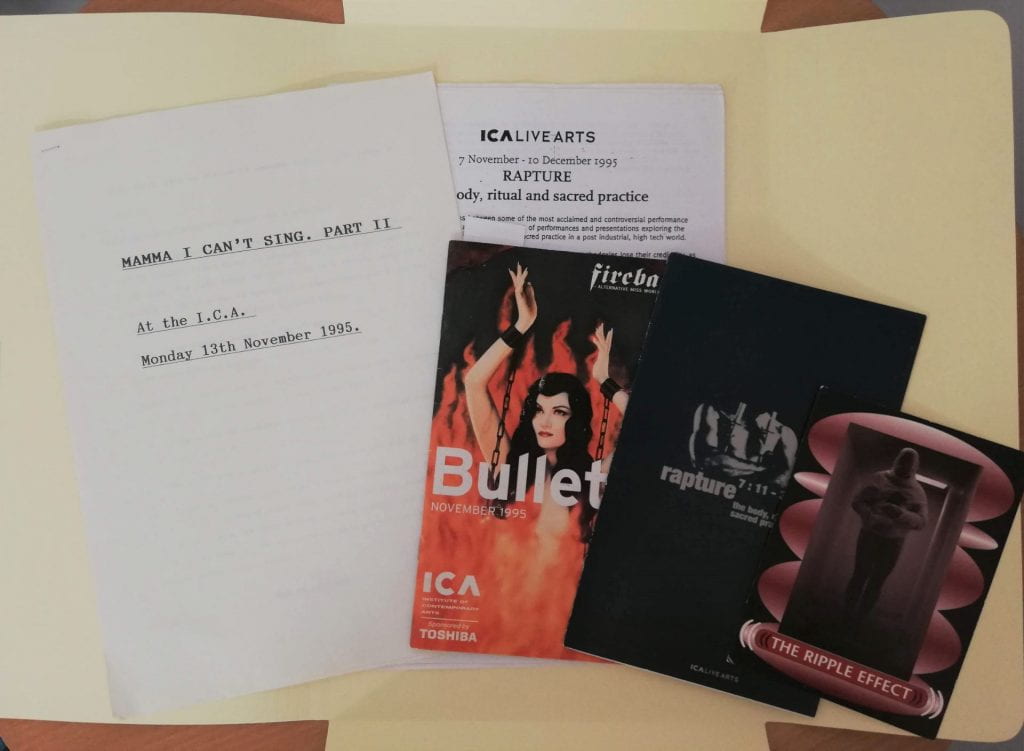

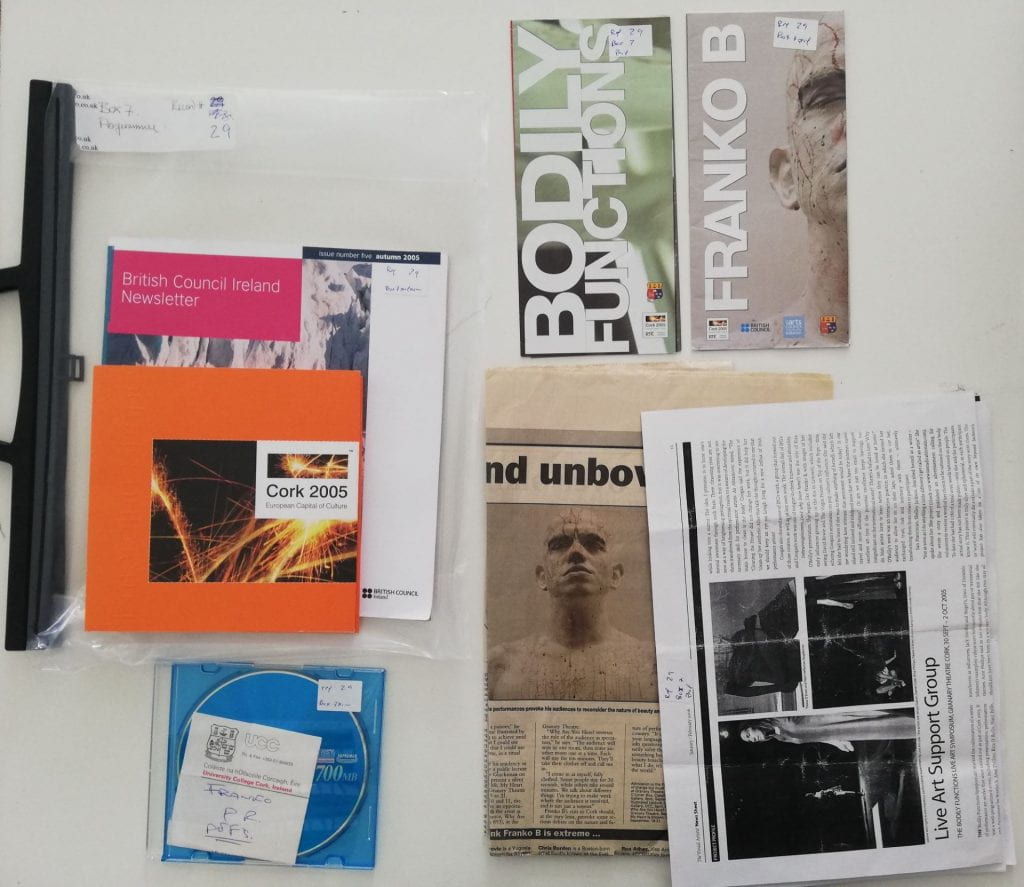

This practice of being alive is made explicit by Franko’s archive: the long processes of his life and work. For every artwork of his that I’ve seen, read about, heard about, or imagined in some kind of public discourse, here are dozens of images, experiments, notes, ticket stubs, flyers, scrawled names and numbers, friendships hinted at, romances recalled, pieces of cloth, pieces of paper, memories, moments and moments and moments collected like bubbles of air in the archive. Like bubbles of air, because they do not make an object but an atmosphere. Like bubbles of air, because they are waiting for your breath.

Breathe them in, absorb these moments, process them in your body and breathe them out. In this way, this archival project requires a vulnerable visitor: arms open, ready to be wounded. In this way, it echoes the workings of art, grief, love, social relations, happiness, emotional excess, memory, forgetfulness and all the other threads of our lives that are not acknowledged in terms of the transaction, the object(ive) or the workings of capital. In this context, every intention is an unanswered question. Every encounter is an unexpected response. How do we talk about all of this? Explicitly (breathe). Vulnerably (breathe). Together? (breathe)

Maddy: who else needs to know about this archive? Who else needs to breathe this air, construct this landscape, be vulnerable here?

The final question for now, Mary. How do we guard against our own fetishisations as we approach the archive from a multiplicity of angles, holding Franko at the centre of our inquiry?

In Freudian terms, a fetish is a type of misrecognition. The fetish object appears to have inherent properties which are, in fact, the properties of the social relations that surround it. Social relations can also produce a fetish: a King thinks he’s a king because other people are his subjects; a subject thinks he’s a subject because someone else is King. And thus a madman who believes he is King is no more mad, wrote the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, than a King who does: both have misrecognised the body of a man as the source of his power.

You could say the same thing about the artist. Or the art historian. Or the art objects that represent their labour.

There is definitely a kind of transfiguration that takes place when you study an art object closely. There’s a painting in the National Gallery of Scotland that I studied so much as an undergraduate, my mind wanders across its surface, sometimes, while I drift into the oblivion of sleep. The painting reminds me of a time when I believed in truths, and discoveries, and a canonical cultural landscape; before I became vulnerable to the explicit mess of subjective relations.

But this is just a story I tell. I know the painting doesn’t embody my feelings about it. I know that if you walked into a small, richly painted room in Edinburgh and saw the Stoning of St Stephen painted in 1603 on copper, it would not mean my dream of intellectual freedom. When I read about you and Katrina finding Franko’s diary, I don’t think the diary holds the value you found. Rather, the value emerges from the ideas you floated together, the relationship you formed, the stories you can tell. And it is in fact this value that holds the diary – makes the pages more tactile, pushes meaning into the gaps between words.

This relationship that you formed includes Franko, imagined in the conversations between you and Katrina, as well as in your private desires to know more. This relationship includes Franko’s intentions, his acts of care, and ego, and preservation that are embedded in this archive. It includes the archivists, the institution, the funders and the other practical supporters of the object you were holding in your hands. And it includes the object.

But it is not the object.

It is a body of relations. An explicit body of relations. Perhaps, an explicit body of relations of care.

What if we start from there?

Or in other words, the answer to your question is in its reverse: holding Franko at the centre of our inquiry, we approach the archive from a multiplicity of angles, avoiding fetishisation.

Maddy – my final question to you: amongst this multiplicity of angles, where are you coming from?