Thomas Manson and George Meredith are playwrights with a particular interest in history and the archive. In 2019 they undertook a residency at the Theatre Collection to explore questions surrounding adaptation and the creative potential of the archive, which culminated in two creative writing workshops. This second blog charts their response to findings in the Julia Trevelyan Oman Archive.

The Julia Trevelyan Oman Archive is one of the most detailed and extensive in the Theatre Collection. Julia – a celebrated theatre, opera, ballet and television designer – kept everything from her art college days onwards. And everything means everything. There are over two and half thousand entries in her online catalogue. The reference numbers which categorise her materials span JTO/1 through to JTO/429. There are boxes full of letters and notes and hurried scribblings. Vast stage plans and intricate sketches. Papier mâché birds delicately wrapped in tissue paper. All the scrappy detritus of a creative life, bound and boxed and labelled in the brimming store rooms of the Collection.

For not only did Julia keep everything, but she also ordered it all properly, and took steps to preserve the incredible wealth of materials she accumulated over the course of her career. As a result, this sprawling collection offers not only a fascinating insight into Julia’s life and work, but also into the act of archive-making itself.

There is a palpable tension in all archives – but particularly this one – between order and disorder. Archives are places of organisation and careful curation, and yet the materials they contain are so often the remains of disordered and unpredictable lives. Take the snippet of autobiographical writing, written quickly in pencil on the back of an art exhibition flyer, that describes a young Julia discovering her passion for creation:

The fascination with gardens grew. From creating imaginative palaces & gardens on the floor from children’s boxes of wooden building bricks, using mirrors for lakes & candlesticks for columns. Magic cities grew and fell as the floor was (JTO/237).

The note ends abruptly, mid-sentence. Julia was disturbed perhaps, or distracted or pulled away by the urgency of some other work. The thought is left unfinished and the paper is left to one side, most likely among the countless other papers in what Sir Roy Strong described as the ‘orderly confusion’ (JTO/112) of Julia’s studio, and this momentary centre of Julia’s creative attention becomes a trace, a relic to be codified and brought into a system of logic unbefitting of such disordered thoughts.

What are we to make of this now in the hush of the Theatre Collection’s reading room? What relation is there between this unfinished thought from some distracted afternoon and the systems of order that define its existence now? And how might a writer exploit this tension? What is the creative potential of introducing, or perhaps it would be better to say re-introducing, disorder to the archive?

Down the Rabbit Hole

We were considering these questions as we came across Julia’s work on Jonathan Miller’s 1966 television adaptation of Alice in Wonderland – a project that crackles with the tension between order and disorder.

As a designer, Julia was renowned for her tyrannous eye for detail and quite obsessive sense of historical accuracy. Her style harks back to the 19th century, with its cluttered, complex, realistic sets. The intricacy and social realism of her designs are actually remarkable given that she was working at a time when most designers of the period were turning towards minimalism in their work. Julia’s work on Alice is no exception. The collection is full of her intricate designs and exacting instructions. There are detailed plans, sections, elevations and drawings. Nothing escapes her eye for detail, and her research and reports cover everything from the placement of the furniture to the patterns on the curtains. Even the flies that will buzz around the Mad Hatter’s tea party are subject to strict controls:

They will live for about a week. Must be kept cool and in the shade. They should be fed on a pasty mixture of sugar and water. We cannot replace them if they are lost. Please return the container. (JTO/6/2).

Such stringent attention to detail seems strangely at odds with the anarchic world it is in aid of. Carroll’s wonderland is a dream landscape, where objects morph and change and disobey the rules of the world as we know them. Invisible cats float in mid-air and babies turn into pigs. Time stops and the Mad Hatter is trapped in an indefinite tea time, while the scones spoil around him. Julia’s geometrical certainties seem unlikely bedfellows with such a topsy turvy unreality.

And yet, in another sense, this cocktail of order and disorder is a perfect reflection of Carroll’s vision. Wonderland is not a world of abject chaos. Order exists, it is simply a displaced form of order that answers to an abstract logic. Eating and drinking in Wonderland has an unexpected effect on one’s size, but Alice soon learns the system and uses it to negotiate her new surroundings. Similarly, the Caucus Race appears to have no rules at all but the creatures participating in it seem to understand the logic, and so Alice plays along:

Alice thought the whole thing very absurd, but they all looked so grave that she did not dare to laugh; and, as she could not think of anything to say, she simply bowed, and took the thimble, looking as solemn as she could (p.27).

The apparent disorder of Carroll’s Wonderland is in fact a satire of the arbitrary systems of order that define adult life in the real world – systems that we blindly inherit and accept without question. For Carroll, these real-world systems are just as arbitrary and bizarre as any to be found in Wonderland.

It struck us that there was a lesson here for approaching archives. Archives are ordered by systems that seem natural and yet are entirely artificial. There is nothing inevitable about the organising principles of archives, and one might just as easily categorise materials by shape or colour. Perhaps by introducing new systems of order and, like Alice, working within the logic of those systems, we can disrupt the dynamics of the archive and find new meanings and creative possibilities.

But what systems? And how can we apply them to our writing?

CURIOUSER and Curiouser

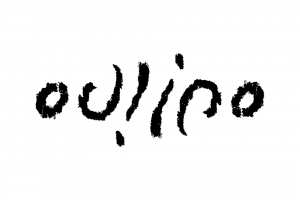

Traversing this precarious boundary between order and disorder, some refuge can be found with the French author Georges Perec and the OuLiPo movement he joined in the 1960s – around the same time that Julia and Miller were making Alice. The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop for Potential Literature) was founded in 1960 by writers and mathematicians experimenting with constraints and seeking different systems of logic for their writing.

Not to be confused with the earlier Surrealist movement, the OuLiPo rejected chance and exalted the imposition of rules. For example, some wrote ‘snowball’ poetry in which each word had to be one letter longer than the last; others forbade the use of letters with ascenders or descenders which hung below or above the line – such as ‘d’ or ‘g’ or ‘y’. These constraints, far from being restrictive, were catalysts for creativity. As Alison James writes: “…the OuLiPo is intrigued by such apparent points of convergence between order and disorder, law and its absence, chance and necessity.” (p.131). Indeed, one of OuLiPo’s founding members Raymond Queneau viewed writing without rules as a form of slavery.

Unsurprisingly, the OuLiPo were great admirers of Carroll. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is full of instances where language and images are disordered and reordered, forming a sort of textual fabric that is open to manipulation and mutation, as if it were a lump of play-dough. Take for example the Mouse’s “long sad tale”, the words of which take the shape of a mouse’s tail on the page. Similarly, the Doormouse’s story about three sisters who drew only things beginning with ‘M’ could be something straight out of the OuLiPo playbook. No wonder the movement described Carroll as an ‘anticipatory plagiarist’ who had been cribbing their techniques long before they had even thought of them!

Carroll’s playful use of linguistic rules and constraints is a great example of the humorous potential of the OuLiPo approach. However, these techniques can also be used for far more profound ends than Carroll’s Victorian nonsense. A famous novel by Perec epitomises how the slippages between order and disorder can prove fertile creative ground to explore even the most serious of themes. La Disparition (literally meaning ‘The Disappearance’) takes the form of a lipogram, prohibiting the use of the letter ‘e’, the most prominent letter in the French language. It is important to note that Perec’s mother died in the Holocaust and his father died fighting in the Second World War. In light of this, Warren Motte points out that “Perec cannot say the words père, mère, parents, famille in his novel, nor can he write the name Georges Perec.” As in Alice, language acquires a material characteristic here, as if it were a fabric to be torn. The destruction of the Holocaust is visited on the materiality of the written word, and the voids at the heart of the family and the self are forcefully evoked through their imposed absence on the page.

The materiality of the written word takes us back to the material archive; a collection of objects arranged by its own system of logic, by order and disorder, with its own gaps, holes and tears. Perhaps if we follow the lead of the OuLiPo, we can challenge its systems and create new orders of our own.

Magic cities

Coming full circle then, we were interested in how we might apply some of these thoughts when directly interacting with archive materials. At the culmination of our residency at the Theatre Collection, we hosted a writing workshop where we explored a number of OuLiPo techniques, one of which is known as larding. Beginning with two sentences (sentences 1 and 3), the writer composes a middle sentence (sentence 2). The writer then adds two more sentences, one between sentences 1 and 2 and another between sentences 2 and 3. The writer continues to lard the sentences until the two sentences have become a paragraph, and that paragraph a page.

This exercise takes the original material and imbues it with renewed meaning; a palimpsestic layering which reanimates the once ossified artefact, ramifying and seeking new connections. We can use this technique, to quote art critic Hal Foster, to turn archival “‘excavation sites’ into ‘construction sites’”, and build new connections from forgotten material (p.60).

For our own larding exercise, we returned to Julia’s archive:

The fascination with gardens grew.

From creating imaginative palaces & gardens on the floor from children’s boxes of wooden building bricks, using mirrors for lakes & candlesticks for columns.

Magic cities grew and fell as the floor was

Using this fragment as a starting point, we built on top of it, adding more and more between the lines until Julia’s unfinished thought became a new and complete piece of writing. And in so doing, we liberated it from the pacifying systems of the archive and re-injected the creative impetus that first prompted it on that distracted afternoon of decades before.

After our workshop, we returned to a small exhibit we had fashioned from Julia’s archive. We placed the items carefully back in their boxes. Sketch books. Photographs. Newspaper clippings. JTO/1 through to JTO/429. Reference numbers and crisp white folders. A trick of the eye, disguising the gaps and chaos and strange syncretism of a life lived somewhere in between order and disorder. Like Alice, and like the OuLiPo after her, we sought to navigate this in between. That fertile, hybrid space where objects look different and magic cities are built.

Works cited

Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. 1865. Oxford World Classics, 2009.

Foster, Hal. Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency. Verso Books, 2015.

James, Alison. Constraining Chance: Georges Perec and the Oulipo. Northwestern University Press, 2009.

Motte, Warren. “Reading Georges Perec.” CONTEXT, vol. 11,

http://www.dalkeyarchive.com/reading-georges-perec/

Items from the archive

‘Magic cities’ from a handwritten note recording the development of Julia’s passion for gardens. Catalogue reference JTO/237.

‘Orderly disorder’ from ‘Spotlight’ article by Roy Strong about Julia, Vogue, February 1971. Catalogue reference JTO/112.

Note about flies from prop list and notes for the 1966 BBC production of Alice in Wonderland. Catalogue reference JTO/6/2.