As part of the Wellcome Trust funded project Challenging Archives: Delivering research access, public engagement and the curatorial care of the Franko B archive, writers-in-residence Mary Paterson and Maddy Costa are engaging creatively with the Franko B archive as it is catalogued, conserved and made accessible. This is the second in a series of blog posts that will reflect on the complex set of challenges the Franko B archive poses, the archival process and Franko B’s artistic practice which explores issues such as the limits of the body and the human condition, dealing with pain, suffering, abuse of power, empathy, eroticism, and sexuality in contemporary culture. In navigating these issues there may be references which some readers find upsetting.

The many lives of performance

by Maddy Costa with Katrina Fray, Ash Rowbin and Mary Paterson

I come to Franko B’s archive without prior first-hand experience of his work, and whenever I feel anxious about this (I ought to know more), I reassure myself that I’m akin with the students, researchers or otherwise curious parties who might encounter it in future. There’s a pleasing detective quality to piecing together knowledge from the stuff of the collection, as though all those years spent watching Moonlighting and Murder She Wrote didn’t go to waste.

For this blog I wanted to talk to students already using the archive for their research, tangentially or directly, to begin to build a sense of the relationships circling around it. Katrina Fray was introduced to me by Julian Warren, Keeper of Digital and Live Art Archives at the Theatre Collection in Bristol; she’s a recent student in the History of Art department at University of Bristol, and focused her dissertation on live art documentation. Ash Rowbin is someone I’ve met at various discussion and performance events in London, and long admired; a BA Drama student at Queen Mary University, he’s writing his dissertation on the political economy of live art, and will be starting a Live Art MA this autumn. Our conversations raised a number of new questions for me, which I’ve addressed at various points to Mary Paterson to consider alongside me.

1. Beyond the object

The helmet sits silent at the far end of the table. Round shape, like a bowl made by children, fingers sticky with glue as they attach squares of papier mache to a balloon. This helmet moulded from canvas, canvas dripped with blood. The stains brown, spattery, more like paint now than bodily fluid, mouthing the words to a story, the story of an art work.

Katrina wrote her final year dissertation on performance documentation, taking as her starting point Peggy Phelan’s much-quoted assertion that: “Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.” I’m immediately charmed by this, because Mary and I have used the same quote both to name and as an ongoing source of inspiration for Something Other, the experimental writing/performance platform we co-nurture with artist and academic Diana Damian Martin. Katrina doesn’t dismiss Phelan’s statement altogether, but instead wonders how the performance, as primary source, can be “amalgamated with all of the other documentation, so you get a better, holistic view of the performance and the different meanings and facets it takes. Photographs, oral history, background things like the tech spec: all of those can tell you something different about the performance.”

This language of “primary source” is, Katrina tells me, typical of the ways in which art historians approach their subjects. “Art history as a discipline can be very, very object-focused,” she says; and, worse, “stuck in a traditional rut”. Its processes are designed for paintings, sculptures, and don’t work for live performance: “You’re completely stumped if you don’t see a performance, or there’s no documentation of said performance.” She wants to see the theory of performance studies infiltrate the study of art history, but also believes that “art historians have a really important part to play in archives and how objects are perceived and dealt with”, that there is much that performance studies can learn from the visual analysis practised in the study of fine art. In other words: “Let’s stop putting boundaries on everything.” Which sounds like something Franko would say.

A similar argument was made by art historian Jonah Westerman in a paper he wrote in 2015 for Tate Research: “Performance happens at the threshold of action and image. That place is impossible to identify definitively, to cordon or sequester, and this is why even the most sophisticated attempts to define performance as a thing in itself end up either submerging it beneath unknowable depths or conflating it with the forms with which it travels.” He resists Phelan’s statement because it creates a definition that works against the radical potential of performance art to resist definition.

Something I particularly enjoy, as I get to know Franko’s work better, is noting the ways in which he resists definitions being applied to his work. On the table before me and Katrina sits a helmet Franko made in 2003 in protest against the Iraq war. Made using canvas from Franko’s “bleeding performances”, it prompts a conversation between the two of us about how art historians might differentiate between “remnants from the performance, and whether you count those as a document or a leftover” – and how this in turn might help to disrupt the term “documentation” itself, which Katrina finds “really problematic”, etymologically too enmeshed in authoritative ideas of proof and instruction. The helmet is engaged in what Katrina calls a “cyclical process”, each new construction creating the means for the next but also looping back to the initial performance. I read in that cyclical motion another resistance, of the linearity and propulsive drive of capitalism, always seeking new markets, new conquests.

Mary, I’m curious where this overlaps with or differs from your own experience, as someone who studied the history of art. What do you still apply from that study, in terms of approaches, questions, principles or practices? What have you since rejected or found to be unhelpful?

2. Serendipity

A sheaf of papers, the yellow-brown of dying leaves. The text typewritten, from the days before ubiquitous computers. Franko’s undergraduate dissertation, starkly titled: The Sadomasochistic Nature of Society. On the third page, a dedication: to my friend Dave. Murdered on 16/8/89 by his next door neighbour, for being a homosexual.

In a box of materials related to Franko’s student years at Chelsea College of Art and Design, Katrina and I stumble across his undergraduate dissertation – written at roughly the age Katrina is now. Scanning its opening pages, I’m struck by the ways in which the questions he raised then – relating to sadomasochistic relationships, private and public expressions and performances of sexual desire, and where these intersect with “social, political economical and moral context/discourse”, not least in terms of classifications and legislation relating to obscenity – are the same questions being raised now in relation to his work and his archive. It’s as though, in that moment of discovery, I have gently pressed my fingers to Franko’s neck and found his pulse.

But perhaps it is Franko’s archive itself whose pulse I’m finding. It seems to grow each time I return to it, and so there is always something there to surprise me.

Mary, one of my favourite stories you’ve told me of your life before I knew you is of being a student in Edinburgh and discovering feminist performance art in the archive. Is this something you went looking for? Or something that found you?

3. Preceding the live

There are papers, perhaps. Someone has them. Perhaps many people have them. But for now the table is empty. For now.

From his undergraduate dissertation onwards, Franko is explicit in articulating another “cyclical process”, that which connects his life, including the politics within which he has lived, and his work in a series of self-informing reinforcing loops. (“The reason I have chosen to write on this subject is because it is the foundation of my very existence, work practice (generally) and sexuality.”) Within the study of art history, however, Katrina identifies a quite separate “taboo”: that against looking at an artist’s intention. “If you’re doing your visual analysis properly,” she reports the thinking, “you shouldn’t need to know it: you should be gleaning everything possible from the object itself…”

As she says this, I see what she means about the “traditional rut” of art history. The object as singular corresponds with the idea of the artist as singular, both in the sense of unlike other (ordinary) people and working alone. I’m still mulling on the implications of this when I meet Ash, who is writing his undergraduate dissertation on the political economy of live art, “the infrastructure or social relations that allow it to happen”. He came to Franko B’s archive in search of a case study: “Historically archives have been a place of acounting and proof [that etymological root of documentation again], and often that’s where the correspondence exists that is especially useful for me.” The academic Diana Taylor, he tells me, writes in her book The Archive and the Repertoire that “what’s found in the archive tends to exceed the live” – which makes me think of Phelan’s somethings other, her differentiation between the ephemeral live act and the effects that exceed it, are excessive to it. Ash’s interest, however, is in the archive as the place where he might find “the things that tend to precede the live: all the things that happen prior – funding applications, blueprints for the set-up – in order for the thing to be made”.

He left Franko’s archive surprised, that it didn’t contain what he was looking for, except in fleeting glimpses. “The archive is always a fragmentary, partial history, as any history is,” he acknowledges. But what does it mean that the partiality of Franko’s archive is so particular? There is very little documentation here relating to the mechanics of staging Franko’s work: the sourcing of canvas and cannulas through which his blood could drip, the labour of the person responsible for painting his body white, for his care following a blood-letting performance, for tidying up the gallery afterwards, all points Ash raises in relation to Franko’s 2003 work I Miss You at Tate Modern.

I remember, on first meeting Julian Warren, him talking about exactly this: his wish that the archive would hold not merely photographs and videos documenting performance – creative remnants, if you like – but everything administrative relating to each performance too. Soon after meeting Katrina and Ash, I have a conversation with a friend, a performance artist, about Beyonce’s film Homecoming; she’s frustrated by how little it shows of “how she actually makes her work. I wanted to hear about the budget! I wanted to see mood boards, things that were cut, how it was cast! Genius is mundane in practice, show me those bits.” As K Austin Collins writes in his review of Homecoming for Vanity Fair:

“Look at the ellipses in how Beyoncé narrates the design of the show itself. […] ‘Every tiny detail had an intention,’ she says. Yet the film never explores those intentions. I wish it had; Homecoming made me long for more of the boring procedural stuff—the meetings, the decision-making, insight into how Beyoncé thinks and feels that’s distinct from how she narrates the story of herself and her intentions. […] Like so many up-close-and-personal looks at Beyoncé, this new special is better at signifying genius than at letting us come close to the real thing.”

Without administrative documentation available alongside creative, Ash argues, the archive risks giving the impression that only the intention of the artist is relevant to the making of the work. “Art histories, especially about performance artists, tend to uphold the idea of the autonomous artist,” Ash suggests. “They tend to give the impression that art just happens and is this autonomous thing that has a life of its own. You don’t get the sense that anyone else was really involved in the creation of the work, of the layers of labour and the divisions of labour that would have had to be in place to do it.”

Mary, around your creative practice you also work as a producer, in finance, on the board of a National Portfolio Organisation: that is, you do a lot of the invisible work that goes into making performance happen. I’m interested in two things here: the ways in which a neoliberal culture deploys invisibility, often to make invisible both the workings of its own power and the machineries of inequality; and also the invisibility of care that makes capitalism possible, whether it’s care for children or those who are too old or too sick to be part of the capitalist machine. You and I have talked about the feminisation of care, and how that is integral to its eradication from view within a patriarchal culture. I’m curious how we can make all this visible in our project, as writers-in-residence with Franko’s archive, how we can question these absences – but also how we can make sure we see them, given their absence, their seeming invisibility.

4. The body as fetish

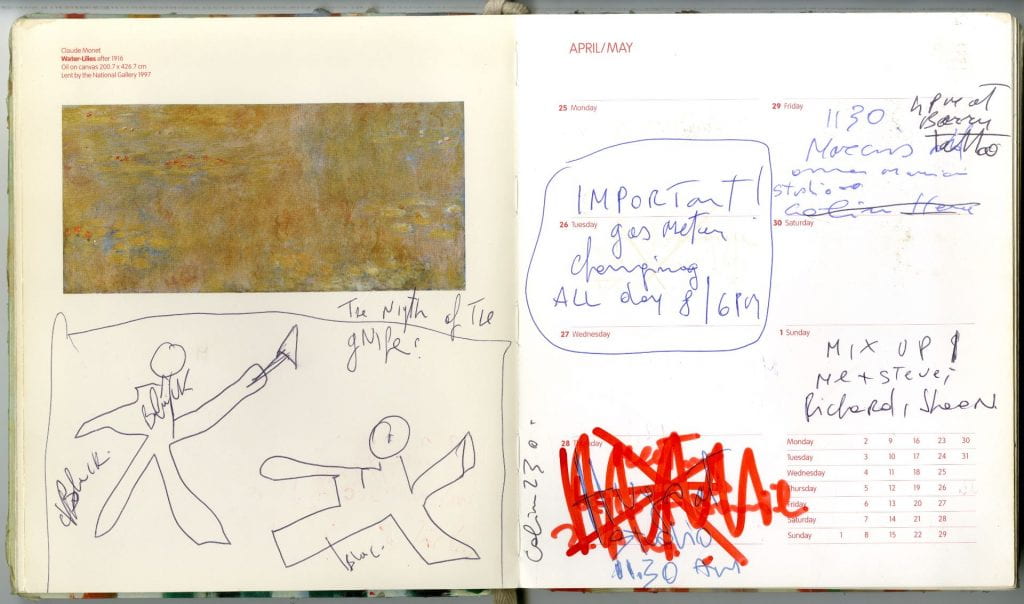

A diary. Square, chunky, thick cover, pastel coloured, the kind given by an aunt or cousin who doesn’t really know what to buy you for Christmas. Paintings inside the left-hand pages, drawn from Tate’s Impressionist collection. Handscrawls barely legible, phone numbers, appointments, a year demarcated into tasks and commitments. An open window, ground level, no curtain or fencing. Stealing into another’s life.

In his search for emails, financial documentation, technical specifications, the behind-the-scenes necessary for performance to be made, I see Ash looking beyond the body: the body of Franko and his body of work. In Ash’s view, this documentation of the social, political and economic infrastructure within which performance sits also consitutes the performance – or what he calls “one of its many lives”. But the fact is, emails and invoices are much less sexy than the body; and I do use the word sexy here deliberately, in the casual sense of alluring, but also with an awareness of the ways in which Franko has always foregrounded sex and sexuality in his work.

Ash tells me of another book, Isabelle Graw’s High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture, which “talks about what happens when an artist moves away from making object-based work and the body becomes material. It doesn’t actually lead to the defetishisation of the object: what happens is that the body becomes the fetish.” Given the ways in which Franko explicitly addresses fetish in his work, there’s something deliciously self-reflexive in this. But it also prods me to question my own feelings in relation to the archive, written to some degree into the first blog post with Mary: of encountering Franko’s body in the archive but wanting to feel connected with it in the flesh. And again, given the ways in which Franko’s work navigates the line between the body as flesh and the body as representation, this desire feels like one he has always deliberately courted, provoked and questioned.

Opening a box from the “Personal” series in the archive, Katrina and I find one of Franko’s diaries, for the year 2005. It’s quite an ordinary day-to-day appointments diary, not a journal of private thoughts but a messy collection of notes and telephone numbers and reminders that the gas man is coming in a frame containing the word IMPORTANT!, so mundane it’s beguiling. We turn the pages of it with as much care and respect as we might a precious sketch book, noting the number of staples slicing into its pages, where Franko had once attached additional notes, enjoying his disregard for date lines and the ways in which he has casually defaced its reproductions of traditional oil paintings, trying to decipher his scrawly handwriting. On our favourite page, Franko has drawn in the white space below a particularly woozy set of Monet water-lillies, two blocky figures captioned with the words “The Nigth of The gNifes”. These are my favourite encounters with the archive: those moments when Franko isn’t in control of his image, when everything becomes slippery.

The final question for now, Mary. How do we guard against our own fetishisations as we approach the archive from a multiplicity of angles, holding Franko at the centre of our inquiry?

Notes and links

The Helmet mentioned in part 1 is catalogued as part of Artwork in the Artwork & Objects series, ref no FB/9/2/10. A digital image of it is available here.

Franko’s undergraduate thesis is from box of Material relating to Chelsea College of Art and Design – BA Mixed Media 1987-1990, ref no FB/1/1/2.

The diary is from the ‘Personal’ series, ref no FB/10.

Jonah Westerman’s essay Between Action and Image: Performance as “Inframedium” was published as a Tate Research Feature in January 2015, and can be read here.

K Austin Collins’s review In Homecoming, Beyoncé Is Closer and More Unknowable Than Ever was published by Vanity Fair in April 2019 and can be read here.