Jill Sullivan, Assistant Keeper: User Services has written a guide to the Theatre Collection resources available to students online.

The Theatre Collection is one of the world’s largest collections of British theatre history and live art. It includes over 140 named collections and archives, comprising artworks, audio-visual material, costumes, designs, set models, playbills, prompt scripts, production notes and programmes.

The size of the Collection can be daunting and due to the current COVID-19 situation you can’t visit us, but here is a brief guide to help you access some of the holdings remotely, as well as some recommended sites to help with your research.

Start with our web pages http://www.bristol.ac.uk/theatrecollection

Then use our guides listed under Explore to find out more about the different collections:

THEATRE

This section is useful for browsing biographical information and finding out more about what each collection holds. It’s organized by theme: Academics, Actors, Collectors, Designers, Directors, Organisations, Writers, and Photographers, as well as ‘Off-stage’ which covers a range of theatre creatives such as producers, managers, critics, agents, and wardrobe staff.

TOP TIP: If a person had many strings to their bow, we’ve listed them by each (for example, Joyce Grenfell was an actor, but also a writer, so she can be found under both headings).

LIVE ART

Live Art is notoriously difficult to categorise. The Live Art Development Agency suggests thinking of live art as a strategy, rather than a category – their ‘What is Live Art?’ web pages are a good place to start. Within the Live Art Archives you can find items relating to performance, art, dance, music, experimental and alternative theatre, poetry, and much more, including a lot of audio-visual documentation. Catalogue records for many of these items are available on the Theatre Collection’s online catalogue, so if you know what you are looking for you can head straight there, but if not a list of individual collections within the Live Art Archives with short, introductory descriptions is also available.

LIBRARY

The library catalogue has a link to the main University of Bristol library catalogue and to a list of our journal holdings. At the moment you won’t be able to access the books at the Theatre Collection, but the University library site will have information and links to electronic books and articles, databases and – NEW – free access to many additional online resources at http://www.bristol.ac.uk/library/find/free/ There are also some excellent newspaper archive websites that I’ll talk about later.

ART UK

The Art UK site contains digitised images of all our oil paintings, which are available to download and use. It’s also a really good site for exploring other UK art collections.

Once you’ve explored these main pages or if you already have a good idea of what you’re looking for, you’ll want to search our online catalogue.

ACCESSING THE THEATRE COLLECTION CATALOGUE

On the Theatre Collection home page, click on ‘Search the Collections’ (left hand side).

On the next page you’ll see a menu on the left-hand side. There’s information ‘About’ the catalogue (and uncatalogued items) and a section on ‘How do I search the catalogue’ which explains the different options.

You can do a basic search in the top bar button, but you’ll probably find the ‘Advanced Search’ and ‘Search by Production’ options the most useful.

TOP TIPS: don’t be too general. If you put Shakespeare in as a search term, be prepared for a long day! Similarly, putting in a theme or concept won’t find results – the catalogue needs facts. Think instead about whether you need to look for a particular play or a character, theatre or actor, or whether you need productions by a particular company for example.

But you might also want to widen the search, in which case you’ll need to do some lateral thinking – for example if you’re searching for an actor, try also searching for the theatre companies they worked for and other people they worked with.

And check spellings as well. Unlike an internet search engine, the online catalogue won’t find versions of words and spellings.

And remember, if you can’t find what you’re looking for, email us if you need help at theatre-collection@bristol.ac.uk

IMAGES

We have lots of digitised images available, although at the moment these are not available to download from our site. If you are a student, then you can email us to request any of these for use in your assignments or projects. Over the following weeks we’ll be working to make more of our images available to view online.

COLLECTIONS

To give you an idea of our holdings, here’s a list of some sample collections:

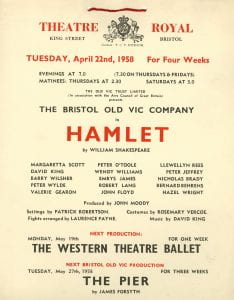

Bristol Old Vic Archive

We hold the archive of the Bristol Old Vic Company from its beginnings in 1946. It includes photographs, programmes, prompt books, production notes and posters. We also have related archives of people who have worked at the BOV, such as the designer John Elvery, and materials relating to the theatre before 1946, ranging from eighteenth century handbills to the in-depth research notes on the history of the theatre created by historian Kathleen Barker.

Have a look at the BOV Heritage pages to see lots of our digitized images and stories from the theatre’s history. And yes, there was a real elephant on stage in the 1820s!

All our BOV and related holdings are now catalogued and we have many more digitised images for use.

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree Business Archive

One of the last great actor-managers of Victorian and Edwardian theatre, this archive contains extensive materials relating to Beerbohm Tree’s management of the Haymarket and Her Majesty’s Theatre. It includes prompt books, photographs, designs, scores, production notes, diaries, financial records and press cuttings books.

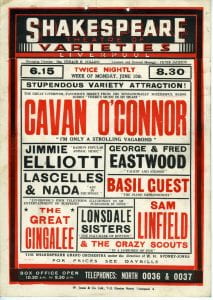

The Mander and Mitchenson Collection

Founded by two actor-directors, Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson, this vast collection represents a passion for theatre and a lifetime of collecting. It took 37 lorry trips from London to Bristol to transport all the items so that gives you a good idea of just how big the collection is! It comprises artworks, costumes, ceramics, objects (ranging from ‘Shakespeare’ tea tins to Sarah Bernhardt’s make up cape, from oil paintings of Kemble and Siddons to ventriloquist dummies!), and nearly 1400 reference boxes containing archive materials on all major UK venues, actors (including ‘Early Actors’ – c.1770-1850), music hall and variety artistes, musicians, designers, directors, writers and dancers, opera and ballet companies, pantomime, melodrama and circuses. These files contain a variety of photographs, programmes, press reviews and cuttings, published scores, playbills and ephemera.

We are in the process of cataloguing the reference files but very little is catalogued to item level. However, we do have some lists yet to be added and there are some digitised images so do get in touch if you can’t find what you need on the catalogue and we can check these for you.

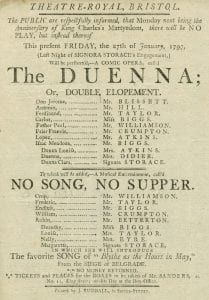

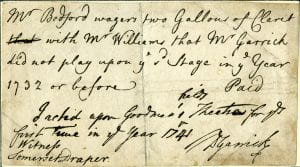

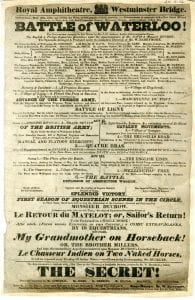

Playbills and Programmes

Playbills and handbills (the precursor of the modern theatre programme and flier) are a mine of information. Unlike the C20th posters, playbills had much more text on them, detailing cast and crew but also scenes and plot synopses. Plus the types of performance, the way they were advertised and the ticket prices and changing names for parts of the auditorium offer a glimpse of the types of audiences that went to the theatre in the past. The Theatre Collection has nearly 300,000 programmes dating from the late C19th to the C21st. Again, these offer fascinating glimpses of social history in the advertisements, and modern programmes often contain detailed articles on the production and histories of the theatre, company and plays.

Interested in modern audiences? Read Dr Kirsty Sedgman’s ‘Lightning Talk’ at the 2019 Theatre and Touring Symposium at https://uktheatre.org/who-we-are-what-we-do/uk-theatre-blog/audiences-behaving-badly-and-what-we-should-do-about-it/

Design Collections

The Theatre Collection contains named archives of specific designers, such as Julia Trevelyan Oman, Oliver Messel (Personal Archive), Alan Tagg, David Walker, Yolanda Sonnabend, John Elvery and Ralph Adron. We also have a generic design collection, which comprises hundreds of set and costume designs, representing over 100 years of incredible creativity. To search for these, you can use the ‘Production’ search option, or the ‘Advanced Search’ option if you know the designer’s name.

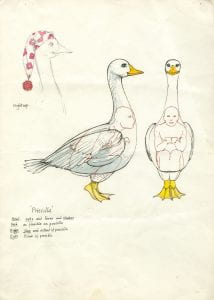

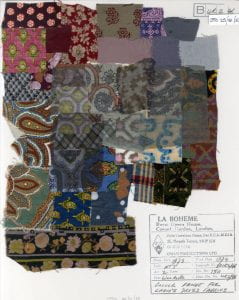

Julia Trevelyan Oman Archive

Julia Trevelyan Oman CBE (1930-2003) was one of the most celebrated theatre, television, ballet and opera designers of the second half of the C20th. She was noted for her attention to historical detail in productions such as Brief Lives (1967, Hampstead Theatre Club and later productions), La Boheme (Royal Opera, Covent Garden, 1974) and Enigma Variations (Royal Ballet, Covent Garden,1968). Her personal archive covers her entire career and includes her original designs with research files, technical drawings and plans, research photographs, production photographs, correspondence and fabric swatches.

Oliver Messel Archive

Oliver Messel was one of the most famous designers of the first half of the C20th, as well as being one of the ‘Bright Young Things’ of the inter-war period. His archive reflects, among other things, his professional achievements as well as his friendships, his architectural designs undertaken when living in Barbados and his wartime work for the Camouflage Unit. His first professional commissions were to design masks for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes production of Zephyr et Flore and for one of C.B. Cochran’s Revues. Among his stage and screen credits were the costume designs for the films The Scarlet Pimpernel, Romeo and Juliet, Caesar and Cleopatra and the set design for Suddenly Last Summer (for which he was nominated for an Oscar), as well as the 1946 production of the ballet The Sleeping Beauty. More information and links to the Messel catalogue are here.

Have a look at our Exploring the Oliver Messel Archive pages, which include an illustrated biography, an opportunity to explore our 2018-19 exhibition Wake Up and Dream (including the audio installation The Caviar Outlook) and a link to watch I Went to a Marvellous Party a performance and installation by Tom Marshman, inspired by the Oliver Messel Archive.

Photographers:

Interested in photography? Take a look at the John Vickers Archive

John Vickers Archive

Vickers trained with the eminent theatre photographer Angus McBean and in turn influenced the work of Mario Testino, his assistant in the 1970s. This comprehensive archive documents Vickers’ career throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Included in the collection are glass plate negatives, prints, framed items, correspondence and ephemera. The Vickers Archive is now catalogued and many of his photographs have been digitised – they are especially strong for productions at the Old Vic (London) in this period as well as portrait photographs of many of the most famous actors of the period.

Live Art Archives:

Performance Magazine Archive

Performance Magazine was the key UK Live Art/Performance magazine from the late 1970s through to the early 1990s and provides a fantastic record of live art activity that took place during this period. The Theatre Collection holds a complete set of the original copies, but the Live Art Development Agency scanned and made available online all 66 issues recently and we’ve included links to these pdfs from our online catalogue so there is no need to wait until we re-open to view these!

Franko B Archive

Thanks to a very generous grant from Wellcome, over the past two years we’ve been busy cataloguing the collection of this extraordinary contemporary visual artist. With over 2,800 detailed catalogue records covering all aspects of Franko B’s practice – performance, ceramics, curating, music, teaching – there is a wealth of material here available for research. Whilst you’ll have to wait until we re-open to access the items physically, there is plenty of documentation available on Franko B’s own website.

Our two wonderful project writers-in-residence, Mary Paterson and Maddy Costa, kept a blog as they reflected on the archival processes we encountered through the project, and you can read their series of blog posts here.

CITATIONS:

If you’re using materials from our collections, please make sure that you cite University of Bristol Theatre Collection. For University of Bristol students, if you’re using the Harvard system you should cite an archive item like this:

Author, Initials., Year. Title of document. [type of medium] Collection, Document number. Geographical Town/Place: Name of Library/Archive/Repository. For example:

Brown, P.S., 1915. An address to the Farmer. [manuscript] Holdbury Collection. 600. London: Holdbury Library.

An in-text reference for the above example would read: (Brown, 1915)

(Source: https://library.aru.ac.uk/referencing/harvard.htm) These guidelines are also available via the UoB Library site here

Remember: we may not be on site but we are available to answer questions about our holdings, or if you need research advice or want to find out more about the Theatre Collection, just get in touch with us at theatre-collection@bristol.ac.uk and we will do our best to help you.

OTHER RESOURCES YOU MIGHT FIND USEFUL:

University of Bristol Library Recommended databases and online newspaper archives

TOP TIPS: You can use word search in this database, but if you’re searching a name, try hyphenating it (e.g. John-Smith) to make the search more specific. Also, if you are searching the theatrical trade journal, The Era, just input Era (not The Era).

The British Newspaper Archive is also a really good resource, with a bigger range of newspapers and twentieth century coverage. It’s a subscription-based resource but with reasonable short-term charges. Visit https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

OTHER ARCHIVES WITH PERFORMANCE RELATED HOLDINGS:

APAC. The association of Performing Arts Collections

All major theatre archives – including the Theatre Collection – are members of this: https://performingartscollections.org.uk/ You can use it as a portal to access information about other collections and their holdings – see https://performingartscollections.org.uk/members/

Bristol Archives

Explore their online catalogue for more information on the theatres and venues of Bristol at https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-archives/

Bristol Old Vic Heritage Project

https://bristololdvic.org.uk/heritage And take a look at the fabulous Limbic Cinema film made for the 250th anniversary of the theatre in May 2016 at https://bristololdvic.org.uk/archive/250th-birthday

National Resource Centre for Dance at the University of Surrey

Including the British Black Dance Archives and the Choreographic Archive of Siobhan Davies Dance. Visit https://www.surrey.ac.uk/national-resource-centre-dance

National Theatre Digital Archive

The archive covers the movement to found the National Theatre and the period from the start of the company in 1963 right up to the present day.

https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/about-the-national-theatre/archive

Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Collections

https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/collections/

SIBMAS (International Association of Libraries, Museums, Archives and Documentation Centres of the Performing Arts)

Similar to APAC, the Members Directory (international) is at http://www.sibmas.org/members/members-directory/

The Live Art Development Agency Study Room and Online Resources

Here you will find library catalogues of LADA’s extensive study room materials, together with a fantastic array of study guides, screenings, audio content, online video channels and project websites, all relating to live art. Available from https://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/resources

University of Kent Special Collections

Including the British Cartoon Archive, the Dion Boucicault Collection, the Charles Dickens Theatre Collection, David Drummond Pantomime Collection and others. See the A-Z listing of all their collections at https://www.kent.ac.uk/library/specialcollections/a-z.html

University of Sussex Special Collections

A range of archives including theatre and performance literature at https://www.thekeep.info/collections/themes/414-2/

Victoria and Albert Museum Collections online, the V&A Theatre and Performance Archives and the National Video Archive of Performance

All at https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/theatre-performance-archives

Remember if you need advice, or want to find out more, just email us at

theatre-collection@bristol.ac.uk and we will try and help.