In 1968, towards the end of a decade renowned for its artistic and musical experimentation, the British stage was, extraordinarily, still bound by strict censorship laws. The Theatres Act 1843 gave the Lord Chamberlain the power to ban any play that may be considered detrimental to ‘good manners, decorum or the public peace’ or heavily modify it, meaning many plays that had had successful runs on Broadway, or elsewhere in the world, could not transfer to the West End.

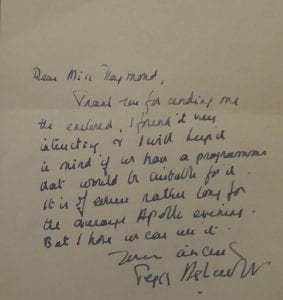

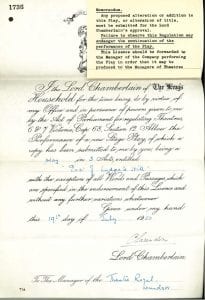

The Lord Chamberlain’s involvement with the country’s entertainment goes back several centuries. Under the reign of Henry VIII, his job was to run the royal household, arrange royal weddings and funerals, administer palaces and look after royal parties. His deputy, the Master of the Revels, was put in charge of in-house entertainments and theatre. In 1737, the Theatres Act devolved censorship directly to the Lord Chamberlain, and in 1843, the Theatres Act declared that one copy of every new stage play be sent to the Lord Chamberlain for review. If it was deemed acceptable, it would be granted a licence like the one below.

The act was vague and the censor was inconsistent, but there were a handful of themes that were absolutely off-limits: God and royalty, it seemed, could never be portrayed. 1.

Plays featuring homosexuality could only be performed in clubs, rather than licensed theatres. The Royal Court Theatre attempted to play the system by changing its status to that of ‘club’ in order to show A Patriot for Me and Saved, but the Lord Chamberlain was incensed and took legal action, winning his case. His victory, however, ultimately led to his demise: the case restarted the debate around the appropriateness of theatre censorship. On 26th July 1968, Royal assent was given to the Theatres Act 1968 which abolished censorship of the stage in the UK, and on 26 September, it came into force.

A year later, Bristol University Drama Department produced The Cornish Ordinalia, three medieval mystery plays, at Piran Round amphitheatre. The Creation play featured God, who was, finally, allowed to be depicted on a UK stage. He is presented as a being with an egg-shaped head, surrounded by a golden crown.

- Changing Stages: A View of British Theatre in the Twentieth Century, Richard Eyre and Nicholas Wright, Bloomsbury, 2001