The Theatre Collection perspective – Dr Jill Sullivan, Assistant Keeper: User Services

As with many cultural and educational organisations, the lockdowns and restrictions during the pandemic meant that the Theatre Collection team had to adjust the ways in which we interact with our users, especially students and researchers. Ideas about online access before Covid were suddenly becoming not only more urgent but also possible due to available funding and the support of the University’s IT Department and Digital Education Office. So it was, that in 2021 the Theatre Collection was able to announce its ‘virtual reading room’. Using a range of visualisers, team members were able to hold meetings online with researchers who were unable or chose not to visit at that time. The visualisers act as real time cameras and a small portable one was particularly effective, linked to a laptop for online meetings where we could show requested items to the researcher. One aspect of these meetings that was particularly useful was the ability to discuss materials with the researcher, identifying documents or pages of particular interest – for scans to be later provided, or for additional searches and follow up email conversations to take place.

In addition to running visualiser meetings ourselves, we also arranged for academic staff to work with the visualiser during teaching sessions, the students joining remotely to see selected materials from the Collection. While responses were nearly always positive and it was seen as a significant progression from simply presenting images on a PowerPoint (although that too had its place), there was an element of ‘trialling’ in this new way of working, and every example of using the visualisers added to our experience and ability to develop and hopefully improve the delivery of remote archive research for our users.

The Theatre Collection supports a range of units across the Faculty of Arts, in particular the Theatre Department, where archives from collections such as the Bristol Old Vic Company Archive are integral to units such as ‘Performing the Archive’ and ‘Performance Contexts’ and we always look forward to welcoming students into the reading room, introducing them to the incredible collections that we hold, and supporting them in their individual research and archival discoveries when working towards their assignments. In the academic year 2021-22 the physical experience of working with archives has been resumed – to the delight of staff and students alike, but there remain instances where the size of a class and the requirements of ventilation and social distancing necessarily caused us to have to rethink how we might run a session that maintains safety in a Covid-aware world while still enabling not just access to the collections, but a worthwhile learning experience.

During the early stages of TB1, Dr Kat Hipkiss and I met to discuss the second year Theatre unit ‘Performance Histories’ and how best we could run it, given the larger size of the seminar groups. The students had spent their first year 2020-21 looking at digitised images in a formal online session or, in the brief periods out of lockdown, visiting individually when able. The cohort were therefore only too ready to actually see the ‘real’ rather than virtual archive items and Kat and I wanted to encourage and enable this as safely as possible. We devised a solution, whereby the students formed study groups to select and request archive items relevant for particular plays and productions. Then during the seminars, with me on hand in the reading room and Kat in the remote seminar room with the remainder of the groups, two representatives from each group came to the Theatre Collection reading room to view the items in half hour slots. The students were shown how to operate the visualiser and they then used it to show and discuss the selected items with the rest of their group. The students (whether those operating the visualiser and working with the actual items or those who had been in the seminar room) were then able to book into the reading room at a later date to explore these or additional items for themselves. This would then enable all the students to have the opportunity of researching the archival materials.

As the half hour bookings progressed and the different pairs of students arrived to join Teams, work the visualiser and share the materials online, it quickly became apparent that this was proving to be really successful. Rather than the session being led by a member of staff, the students were being handed the responsibility of selecting items and effectively running the sessions, responding to and working collaboratively with their peers in the remote seminar room. Beyond liaising with students beforehand when items were originally being requested, and explaining how to work the visualiser, I actually had minimal input, although remaining nearby in case of problems or questions. In the seminar room, Kat was similarly able to answer or encourage questions. However, the students were clearly enjoying being in control of the process and the excitement of discovery and the enthusiasm for exploring items with guidance from their peers rather than staff, was palpable. Using a visualiser enables an ‘over the shoulder’ visual experience for the remote user and the students were quick to find and use features of the visualisers such as the zoom and rotate functions to pick out details and raise questions.

These sessions gave us an incredibly valuable insight into the way we might continue to work when needing to engage to some degree with remote learning. Combining research of the ‘real’ archive items with a student led process enabled it to be seen as not just another online learning tool, but an active and, importantly, collaborative process in which students took ownership of the learning experience.

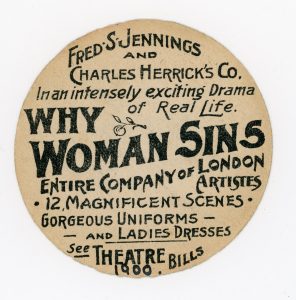

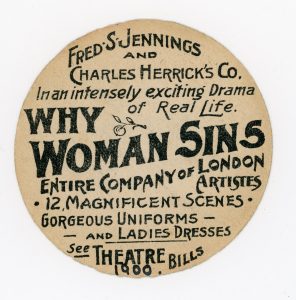

Front and reverse of an advertising card for the melodrama ‘Why Woman Sins’ (MM/2/TH/SU/ML/1). Using the visualiser, students found that the apple created a 3D perspective.

The Tutor’s perspective – Dr Kat Hipkiss, Theatre Department

When I became the lecturer and seminar leader for the second year Theatre Studies unit ‘Performance Histories’, I asked each student to tell me their favourite thing they had studied so far and then what they were looking forward to most. A large proportion of them said they were most looking forward to the Theatre Collection sessions. There was something in their eagerness to get into the room, to physically interact with the archive and relish the materiality of items, that felt prompted by the digitisation of the world over the past few years. However, there were still Covid concerns to consider, and we needed to be aware of how best to balance these with the students’ enthusiasm for the material archive. It also emphasised to me how much I wanted to ensure that students had ownership over the process as much as possible, looking at the items they wanted to look at, in groups they themselves had formed based on their own research interests.

In order to ensure student and staff safety in the Theatre Collection, Dr Jill Sullivan (Assistant Keeper) and I devised a plan of having two representatives of each presentation group in the Theatre Collection whilst the rest were in the seminar room with me. Each group would have 30 minutes, and through a Teams meeting, would look at and discuss the items that had been requested. We hoped that this would enable that balance between keeping everyone safe, whilst also providing access to the material and giving students’ ownership of their research.

This approach required set up and preparation before the students went into the Theatre Collection. Students were shown how to use the Theatre Collection online catalogue to search for and request items, though what they requested was left open for each group. Jill also virtually attended the whole cohort lecture on the week of the Theatre Collection visits to demonstrate how to use the visualiser over a Teams meeting, so that when students went to their sessions, they knew how to operate it.

Importantly, there was also a theoretical setting up of the Theatre Collection sessions, as throughout the unit students had been asked to critically think about constructions of history and the role of the archive, including (on the week of the TC sessions) reading Rebecca Schneider’s ‘Performance Remains Again’ (2012). This preparation meant that, although students may not have known what they were looking for, they were more aware of how to look for it and how to think about it critically.

When it came time for the in-class 30 minute Theatre Collection visits, it became clear that students were prepared to take ownership over their session and the visualiser technology. The students in the seminar room with me would guide those in the Theatre Collection, asking questions about the items in order to narrow focus and draw attention to certain parts (such as ‘what does it say on the back?’; ‘can you zoom in on that part?’; ‘is there anything else like that one?’). Often those in the Theatre Collection would get excited about particular items and build a sense of anticipation for those in the seminar room. It was particularly apparent how comfortable the students were with the visualiser itself, utilising functions such as the zoom or rotate to get the most out of the material, sometimes affording what felt like a privileged view for those in the seminar room. Yes, they were not there with the item, but they were getting a zoomed in picture projected onto the wall of the classroom. Often students would move right up to this projected image and interrogate the small details that now were the same size as them.

After the in-class sessions had finished, it was clear how much the technology had impacted how the groups worked. Those in the Theatre Collection quickly became effective in communicating what they had in front of them and what was coming up next. In most cases there were two students in the Theatre Collection, and they worked together with one operating the visualiser and the other prepping the appropriate materials for what would be looked at next. Because of this, the visualiser became the place where the most interesting, detailed, and relevant documents were presented by those in the Theatre Collection to those in the seminar room. The fact there had to be the visualier meant that there was an active filtering of material in order to use the 30 minute slot most efficiently. This enabled students to be a lot more specific in what they were looking at (even if when started they did not know what they were going to be looking for or what their argument was going to be). It meant they had to hone in on something they found interesting and interrogate it as a group, forming arguments as they went, as opposed to all looking at different items and forming individual arguments about them. The use of the visualiser necessitated communication and group focus, and meant that by the end of the 30 minutes, each group had a short list of items they were going to consider further and the basis of a critical argument.

All groups used items from the Theatre Collection in their final presentations for the unit, and each also used their work and conversations from the remote visualiser sessions in their central arguments. From my perspective as a teacher on the unit, the visuliser sessions were highly successful. Not only did the visualiser allow students to use the archive in a Covid safe way, but the technology itself created both constraints and opportunities that helped shape the students’ experience of the Theatre Collection.