DV or digital video tape is a format that was launched in 1995 and remained popular until the late 2000s. There are a few varieties of this type of tape but I want to discuss the consumer format known as MiniDV.

DV technology brought a considerable jump in quality from previous camcorder formats such as VHS and Hi8 with more compact and relatively affordable equipment. This made MiniDV a popular choice for arts organisations to document their work so we have a lot of these tapes in our more contemporary theatre and live art collections.

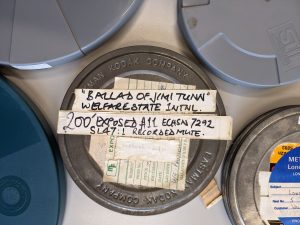

During 2023/24 I worked on the preservation of the audiovisual material in the Rideout collection which includes around 150 MiniDV tapes. Rideout, subtitled Creative Arts for Rehabilitation was established in 1999 by Saul Hewish and Chris Johnston to develop innovative, arts-based approaches to working with prisoners and staff within UK prisons.

The condition of the tapes indicated that they had been stored fairly well with no signs of physical damage or mould which can often be a problem when tapes are stored in conditions with varying temperature and relative humidity.

The process of preserving the audiovisual material on DV tapes involves copying the digital information encoded on the tape to a digital file on a computer. This differs from the process for analogue tape such as VHS which requires a digitisation process i.e. analogue to digital conversion. Copying the data from tape gives the optimal audiovisual quality and also has the benefit of retaining metadata such as the time/date of the recording, camera settings used, and error information. The tape must be played back in a suitable DV playback machine aka “deck” or camcorder in real time and the digital information on the tape can be copied directly to a computer using a Firewire cable connection or IEEE 1394 to give its correct technical name.

The first challenge is that Firewire technology is obsolete. It used to be a fairly standard interface, especially in Macintosh computers but now you need to install a Firewire card to your computer or use some kind of converter cable. We use the first option.

The second challenge is that playback decks or camcorders for DV tapes are no longer manufactured so second-hand units must be purchased. The price for professional decks is rising as the demand for preserving DV based material increases. We currently have four pro decks which all need occasional servicing to keep them running properly. Engineers familiar with this type of equipment are also getting harder to find.

So we have our deck, firewire cable and computer – this is the basic equipment needed to copy DV tapes. I also use a video monitor, amplifier and speakers to monitor the off-tape signal directly during playback.

Another challenge I discovered with this particular collection of tapes was that a fair proportion of them had been recorded in long play (LP) mode. None of my four professional DV decks are long play compatible so it is not possible to make a good quality digital copy of those tapes with them. There are a couple of professional decks that will play long play tapes but they are extremely hard to find and are accordingly very expensive. The solution was straight forward – most Mini DV camcorders will play Long Play tapes back well and are still an affordable option (£100 or less on eBay).

One of our main challenges with the tapes themselves is that they are prone to errors caused by signal dropout of video and audio from dirty or damaged tape. DV uses a technique called error concealment to try to disguise this dropout – this can include replacing the affected area with the same corresponding pixels of the previous frame or next frame (most common). Sometimes this strategy works so well that it is not noticeable in the resulting file, especially with static frame shots that contain a high degree of visual similarity from one frame to the next. However, when there is lots of movement, error concealment can cause the image to appear glitchy or blocky.

Audio errors can result in jarring clicks or loss of signal. Sometimes fast forwarding or rewinding a tape can remove errors, on other occasions manual cleaning of the video heads may be required. Even where the errors cannot be eliminated by these methods, tapes often don’t behave consistently when played back – they can display errors over certain sections and on subsequent plays fail to display the same errors or show errors in different sections of the tape. This behaviour can actually be used to our advantage in creating the best preservation copy possible which I will explain shortly.

In order to copy the information from the tapes to create our digital preservation files we need suitable software. Most Non-Linear Editing (NLE) software packages including Adobe’s popular Premiere Pro no longer support tape-based workflows. There are some older freeware options but these are no longer technically supported and can be unstable or unavailable for certain operating systems. Thankfully, the international community of video archivists and engineers has come to the rescue (literally) with a versatile free open-source solution called DVRescue. Open-Source means that end users and developers have the freedom to study, improve and redistribute the software.

DVrescue supports many of the commonly used professional DV playback decks and its capture interface displays timecodes, time & date of recording as well as a real-time graph of errors detected during the capture. Once your tape capture is completed the software has an analysis tool that pinpoints the position and nature of each error so that you can examine the effect on the video/audio in your file. Finally, there is the option to package the captured raw DV stream into a suitable file container – we use Matroska which is an open standard media container commonly used in video archives.

There are additional features in DVRescue that can be accessed via the command line, most useful of these for me is the merge function. This allows you to take two or more separate passes of the capture and combine them. The process takes advantage of the inconsistency of error display on subsequent plays, mentioned earlier, to return one file containing the best frames from each pass. By capturing short sections of video over known error regions and merging these with your master capture you can create the optimal preservation file.

So far so good, we have a set-up that can optimise our DV captures and produce greatly improved results from previous workflows. However…remember those Long Play recordings I mentioned earlier? The ones we have to play back with a camcorder? Well the camcorder is not supported by DVRescue so we have to use an alternative capture software. I use a discontinued software called Scenalyzer for Windows, this doesn’t have any of the sophisticated error reporting or analysis tools present in DVRescue but it does allow us to capture the tape in AVI format and retain the recording’s metadata. The files can then be analysed using a standalone piece of open-source software called DVAnalyzer. Errors can be identified and located and further corrective tape passes can be made. The resulting files must be converted to a raw DV stream before they can be merged with DVRescue to produce a best quality master copy. This conversion is done using an open-source command line tool – FFMpeg. We can then merge the files as before and re-package the master to a Matroska container.

So we have our workflow for producing preservation copies of these digital tapes. This is all great as long as your tapes are behaving but amongst any collection of DV tapes you will inevitably find problems.

- Tapes that are dirty. Playback may be improved by cleaning – I do this by using one of my decks that I can open up to access the tape path, I then hold a special cleaning swab lightly against the tape and fast forward and rewind it. This isn’t always successful but has definitely improved the performance of some tapes.

- Tapes causing “head clogs” – within seconds of playback the picture and sound will drop out due to particles shedding from the tape. The deck will not play back any tape until the heads have been manually cleaned. Cleaning and sometimes “baking” i.e. heating the tape to 54°C for a few hours) can improve performance. Where the head clogs are severe, tapes will have to be captured in sections with manual cleaning of the heads in between – a laborious and time-consuming process.

- Damaged cassettes – the cassette shell may be damaged and prevent it from playing back or even being accepted by a deck. For these, the tape reels can be removed and transferred into a replacement cassette shell to achieve playback. Due to the size of the tapes this can be a fiddly process.

All that remains after our digital preservation copies have been produced is to create access or viewing copies for each file. These are smaller, more manageable files suitable for easy playback or sharing. I create these using a Non-Linear Editing (NLE) Software e.g. Premiere Pro or Shotcut which allows me to make adjustments for optimal viewing before creating the access copy file. All the digital files are then securely copied to and stored on the university’s Research Data Storage Facility.

I’m happy to report that I’ve managed to produce digital preservation copies of every DV tape in the Rideout collection. Some are perfect with no errors whatsoever, the majority have a few minor errors which may or may not be noticeable and just one has substantial errors throughout, although most of the contents of the tape can still be viewed and listened to. A fair bit of painstaking work was carried out to preserve the collection but I believe the additional effort required to get the optimal results is well worth it. Overcoming the challenge of obsolescent technology to preserve and do justice to these unique cultural works and their creators brings its own rewards.

Nigel Bryant – Audiovisual Digitisation Officer, University of Bristol Theatre Collection