A couple of weeks ago, the Theatre Collection was offered the opportunity to trial 3D photogrammetry on selected objects from the collection. This opportunity was courtesy of Cyreal, a company who specialise in this process, creating accurate digital 3D models of objects for the cultural heritage sector. The Theatre Collections team selected objects to photograph from the Oliver Messel Archive and the Franko B Archive; two collections which include a variety of different objects, art works and costumes. Also included were examples of ceramics (from the Mander and Mitchenson collection), costumes (including Stephanie Cole’s costume from the TV series Tenko) and set models for Cinderella and Look Back in Anger.

Oliver Messel was one of the most famous (and highly paid) stage designers of the early twentieth century, working with actors including Vivien Leigh, Diana Duff-Cooper, John Gielgud and Ruth Gordon and dancers including Margot Fonteyn, Robert Helpmann and Tilly Losch. Messel designed for theatre, opera, ballet and film, with the Oscar-nominated Suddenly Last Summer his last film. In between these productions he also designed fabrics, publicity material, furniture and interiors. Notably, in the 1950s Messel designed two sets of rooms for the Dorchester Hotel, a bedroom suite which became the favourite hotel suite of stars like Elizabeth Taylor and Marlene Dietrich and a set of function rooms on the eighth floor. On moving to Barbados in 1966, Messel began a further career as an architect, designing many villas in Barbados as well as setting the direction for the design of the nearby island of Mustique with his design for many of the villas as well as the Cotton House hotel and proposing designs for village houses, shops, churches and schools on the island. The items photographed by Cyreal from the Personal Archive of Oliver Messel represent various aspects of his career including a Hungarian folk costume, acquired by Messel during a research visit to Budapest in the 1930s while working on the Ivor Novello production Glamorous Nights and examples of the moulds he made to illustrate his architectural proposals.

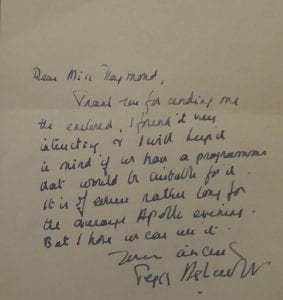

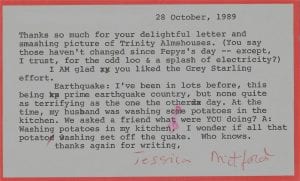

The Franko B Archive covers the last 30 years of the work of internationally renowned performance artist, Franko B, forming part of the Live Art Archives of the Theatre Collection. The archive contains material related to Franko B’s intense body-based live art performances, as well as his visual art, exhibitions, screenings, publications, collaborations and his work as a mentor. Donated to the Theatre Collection by Franko B in 2008, the archive is a complex mixed media collection including audio-visual material, photographs, posters, printed reviews and over 30 objects that featured in performances or exhibitions. Three objects were selected from the archive to photograph, all of which have featured in exhibitions, including a Helmet and Coat Hanger, created with canvas from bleeding performances, such as I Miss You (1995-2005) and Still Life (2003-2006). Also chosen, were a Pair of Boots designed by Lee Benjamin and featured in Oh Lover Boy: The Exhibition (May-Jul 2002). The boots form part of the collection of Haute Couture clothing (1998-2008) created in collaboration with designers utilising the canvas from Franko B’s bleeding performances. Other items of clothing from the Haute Couture collection are also part of the archive and could be 3D photographed in the future if an opportunity was to arise.

The 3D photogrammetry rig featuring multiple DSLR cameras, turntable, backdrop and lighting was set up at the Theatre Collection by the Cyreal team. The mobile rig could easily be reconfigured depending on the size of the object. After placing an object on the turntable and a few clicks of a mouse, the fully automated process begins. With each move of the turntable, the DSLR camera shutters are triggered, which is repeated until a full rotation of the turntable is complete. The process takes around five minutes for each object rotation, which was repeated for certain objects to ensure all angles were captured. Within that short amount of time the cameras capture all the data required to create an accurate digital 3D model or in the case of some of the costumes, a 360° image.

These digital representations of the Theatre Collection objects can now be viewed online via the 3D Gallery on the Cyreal website. Each object can be rotated and manipulated so every angle can be viewed. This photographic technology allows for much wider engagement with the collections beyond the Theatre Collection’s Reading Room. The trial allows us to show costumes from all angles as well as allowing viewers to tilt and turn set models to examine them from angles we simply couldn’t allow with the original object. Digital representations have the potential to be used in multiple platforms such as Virtual Reality or Augmented Reality, which could be used as an innovative teaching resource, with every student in a classroom able to access and interact with a digital 3D version of an object via a phone or tablet. This trial offered us the opportunity to see how 3D photogrammetry works and how it could be used to create a new level of engagement with the collection.

The personal archive of Oliver Messel was purchased by the Theatre Collection in 2014 with the help of grants from the National Heritage Memorial fund, the Friends of the National Libraries and others. It is currently undergoing cataloguing and conservation thanks to generous grants from the Heritage Lottery fund, the Linbury Trust and others.

Cataloguing and conserving the archive of Franko B has been made possible by a Research Resources grant from the Wellcome Trust awarded earlier this year. The project, Challenging Archives: Delivering research access, public engagement and the curatorial care of the Franko B archive will run for two years, culminating in a public exhibition and symposium in 2020.