It’s been nearly two months since my last blog post, and during my hiatus, my designated placement time with the Theatre Collection has been spent developing my research skills, as well as learning more about archiving and museum curatorial practices with Jill Sullivan (Assistant Keeper: User Services) and Athene Bain (Archives Assistant). These conversations have brought up some important context and theory behind archiving, as well as thought-provoking considerations about the preservation and access strategies of archives and museums. Furthermore, my gained understanding has supported my artistic process as I’ve begun to synthesise connections between particular archive items of interest, leading towards the creative conceptualisation and design of my performance.

My research has been guided by my exploration into the presentations of memory in theatre, either in the content of the play itself or discovered within the memories of the people who made and enjoyed theatre. I’ve paid particular attention to the visual materials such as photographs of actors, costume designs and set models, but I’ve unexpectedly been thoroughly engaged –and at several moments, entertained– by the written archives, more specifically letters.

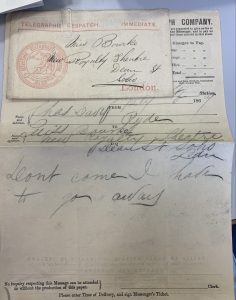

I was helpfully directed to the Jessie & Annie Bourke Collection of correspondence (Reference: BTC80), five boxes of letters detailing the professional careers and later lives of Jessie, her sister Annie, and their cousin Eva Watson, actresses of the 1860s and 1870s. In this unique collection, I found a single telegraph addressed to Annie Bourke to be particularly intriguing. Characteristically short, I spent quite some time trying to decipher this cryptic message, and its greater meaning between the lines of the faintly penciled cursive.

An uncatalogued item in BTC80 Box 1: a telegraph addressed to Annie Bourke that reads ‘Don’t come, I have to go away’

My mind instantly wandered; I began to wonder whether this message was a simple warning that Annie would be met with disappointment at a previously agreed upon meeting spot? Or was this note emotionally charged, with unwritten but potentially weighty cause behind the sender’s impulse that they had no other option than ‘to go away’? Alongside the manifold number of long letters addressed to Annie – some even addressed to the name of the character she was playing on stage at the time – these letters allude to the intense adoration male audience members had for their favourite actors and the discomforting tension between declarations of admiration and harassment. Did Annie keep the reason for this telegraph in her memory? Did she remember the letters from her many admirers? Did she have favourites? Were there admirers whom she genuinely admired back, or whom she charmed for her own pleasure as the subject of adoration? Without her own responses, documented in the letters she did or did not send, we can never know. Moreover, I had found this moment of wonder to be incredibly formative for the devising process of my performance.

In addition to the sector knowledge and skills I have acquired, I have also learnt a hard lesson that any researcher must accept: unfortunately, it is impossible to see or research everything. Whilst I allowed myself time to explore tangential archive items, given the time constraints of the duration of my placement and my own time management between my final year units, I had to decide what leads I wanted to pursue and which I regrettably had to leave behind.

My direction of research has not been linear these last few months, but despite the twists and turns, the journey has been productive and, most notably of all, joyfully absorbing. Supported by Jill’s knowledgeable suggestions, I feel I have a solid foundation of research to begin to build the design conceptualisation of my performance, which I will share with you in my next post.