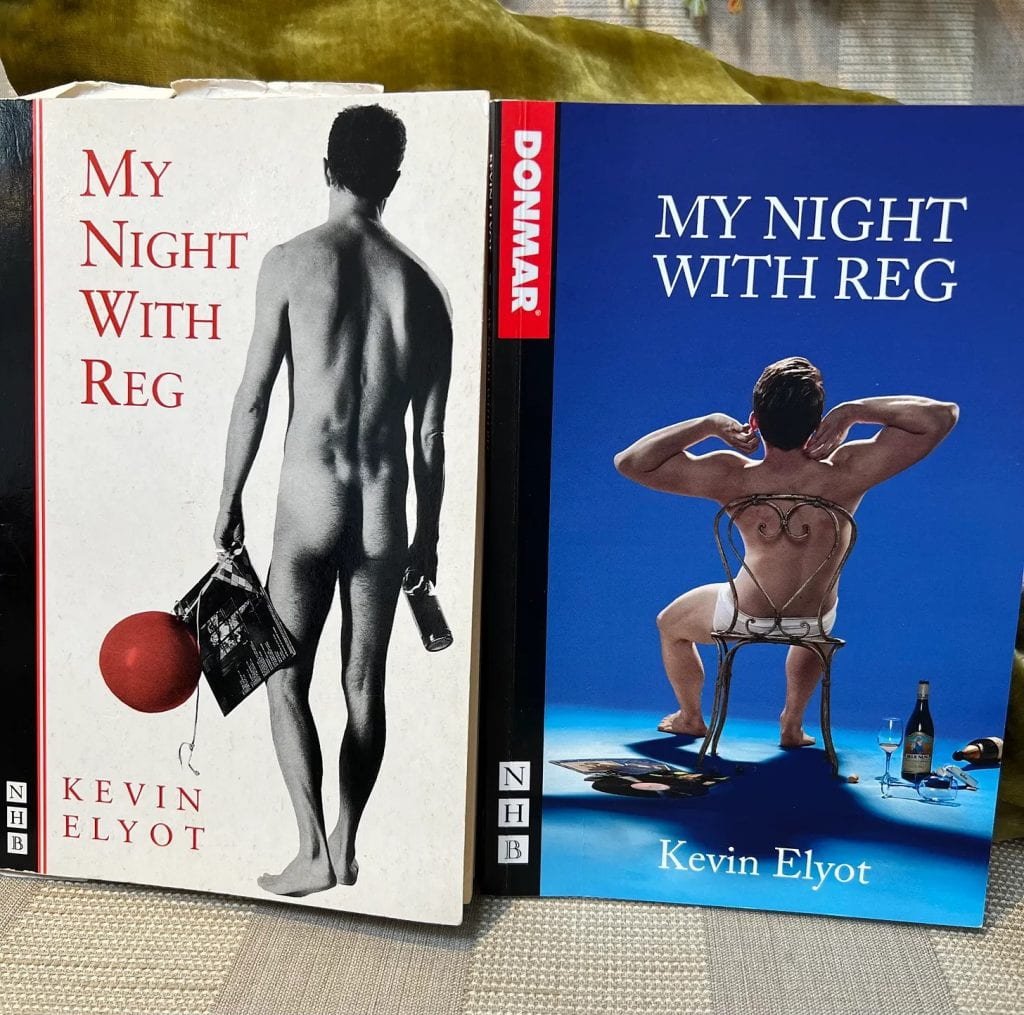

Samuel Adamson is the current recipient of the Kevin Elyot Award, an annual award given to support a writer-in-residence at the Theatre Collection. It is given in memory of the renowned playwright, screenwriter and Bristol Drama alumnus, Kevin Elyot (1951-2014) and the influence he has had on writing and the Arts. The award has been generously funded by an endowment given to the University by members of Kevin’s family. The endowment was gifted along with the Kevin Elyot Archive, which is held at the Theatre Collection, and comprises scripts, correspondence, manuscripts and publicity material detailing Elyot’s working process from initial idea to finished product.

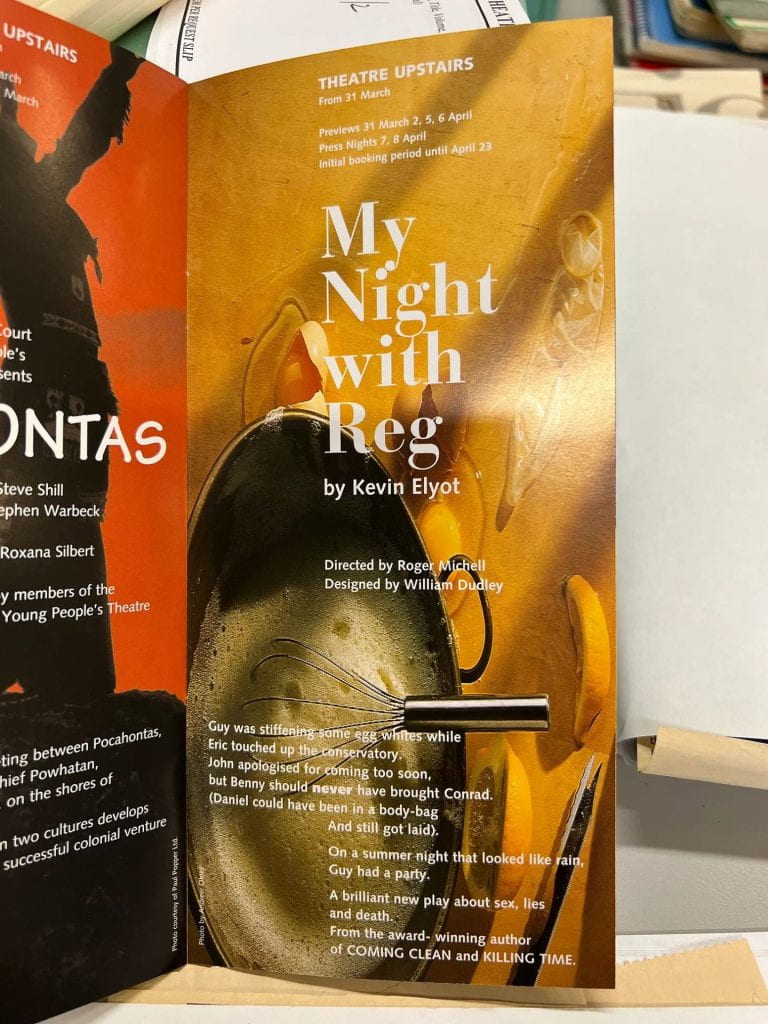

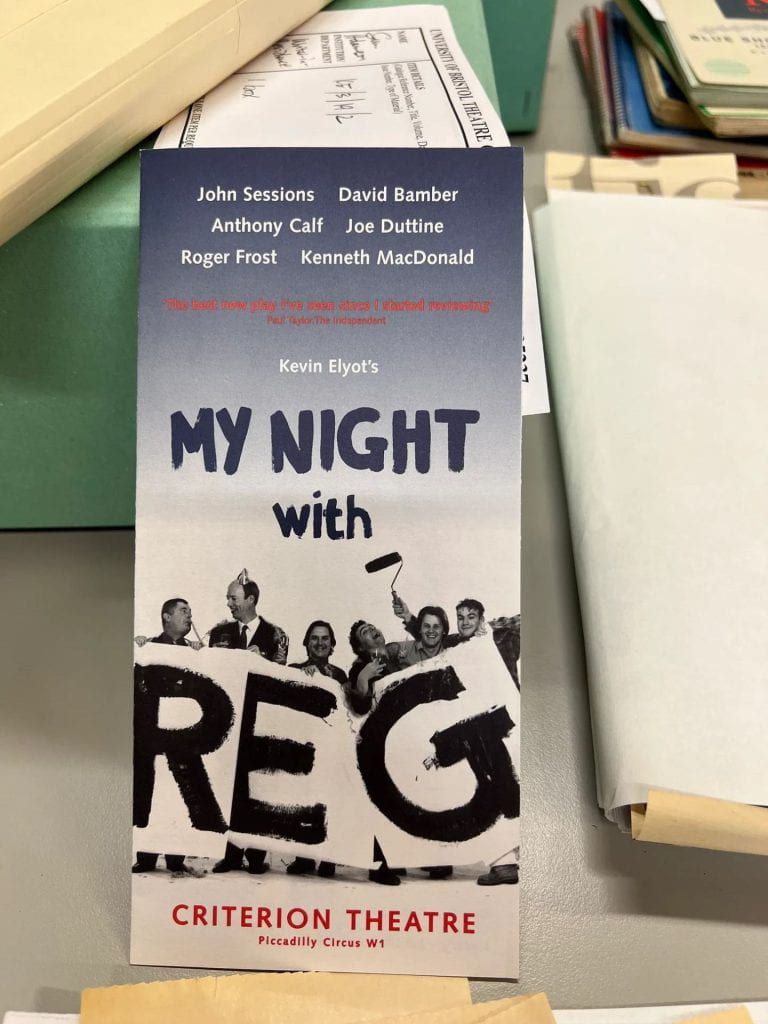

One summer’s day in 1995, I met my agent Sebastian Born for the first time. After our meeting in his office in London’s Holland Park, he joined me on my walk to the Underground and on the way told me something about his client Kevin Elyot’s My Night with Reg. This play – which had premiered to huge acclaim at the Royal Court Theatre in March 1994, was still doing great business in the West End, was in development as a film for the BBC, and was attracting interest from around the world – had been rejected by Hampstead, the new-writing theatre that had commissioned it.

Sebastian is a phlegmatic man, and over the years I’ve interpreted his story as a lesson to me, the smug young playwright who’d just secured an agent. The theatre is fickle. Some people will like your work, some won’t. Nobody knows anything. Be philosophical about the inevitable disappointments if you can.

Still, there was a faint trace of ‘sucks to Hampstead’ in Sebastian’s tone that at the time I relished as I’d seen My Night with Reg three times and considered it a work of genius.

My memories of Roger Michell’s original production are vivid. It starred David Bamber, Anthony Calf and John Sessions as Guy, John and Daniel, old university friends and gay men living in the shadow of Aids. I remember Bamber’s perfectly timed delivery of the play’s first double entendre: ‘I was just stiffening some egg whites.’ I remember the friends roguishly raising their glasses to ‘sodomy’. And I remember, after Aids had killed both the title character and Guy, the terror behind Daniel’s line to John, ‘I’m suddenly very tired,’ and John’s deceptively simple response, which, from Anthony Calf, was in fact a primal scream: ‘I’m pretty tired, too.’

I also remember my excitement as I realised that Reg, Daniel’s boyfriend – who like Samuel Beckett’s Godot never appears – has slept with every character except Guy, the self-conscious single man at whose flat-warming the story begins. Whether Reg has passed on HIV to the others is ambiguous. What is unambiguous is that Guy, who harbours a secret love for John and barely sleeps with anyone, contracts HIV after being raped in Lanzarote by ‘a mortician from Swindon.’ In one of the play’s deftest structural conceits, the character who does not have a night with Reg is the only character who dies.

As the 2023 recipient of the Kevin Elyot Award, given annually to support a writer-in-residence at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection where Elyot’s papers are housed, I’ve learned that Elyot was proud of this superior craftsmanship. ‘[T]he STRUCTURE is a COUP!’ he wrote in one notebook – and the play does indeed have two coups de théâtre when time jumps forward and Guy’s flat-warming becomes a wake: first for Reg, then for Guy himself.[i] Elyot storms his comedy of manners with tragedy, and it is surprising, thrilling and heartbreaking. Reg is a funny play about serious things: the randomness of disease, the necessity of lies, the pain of unrequited love – and the cruel threat to gay men’s sexual freedom after the liberations of the 1970s (the subject of Elyot’s first play, Coming Clean, which premiered in 1982, just before the Aids crisis).

In 2004, Sebastian Born retired from agenting, and at his farewell party at a bar in the Portobello Road, I noticed Elyot. I wanted to approach him and say how much I admired Reg, as well as Coming Clean and the two other plays I’d seen in their original productions, The Day I Stood Still (National Theatre, 1998) and Mouth to Mouth (Royal Court, 2001). I wanted to say how much I was looking forward to his new play Forty Winks, due to open at the Royal Court that October. I wanted to say I was looking forward to many more plays.

Unfortunately, like Guy in Reg, I was too self-conscious to act on my desires – though I went to Forty Winks, which, sadly, was the last of Elyot’s plays to be produced in his lifetime (he died in 2014 at the age of 62; his sixth play Twilight Song premiered posthumously in 2017). Forty Winks is a troubling piece, inspired by the Don Juan legend and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s extraordinary 1968 film Theorem. Although these references are explicit in the text, most critics missed them, and felt that Elyot was repeating himself. It was his least successful play.

If Isaiah Berlin is right that writers are either foxes who range over a large landscape, or hedgehogs who stay close to home, then Elyot, like his hero Proust, was a hedgehog. In the last ten years of his life, he adapted nine Agatha Christie novels for ITV and Christopher Isherwood’s Christopher and His Kind for the BBC – all to considerable acclaim. But it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that he was hurt by the failure of Forty Winks, and by the critical insinuation that he lacked the ambition of a fox. His papers are full of reminders to disregard critics, and one is striking: ‘FORGET fashion, what’s expected, comedy per se, rivals – WRITE what’s true, what’s true to you, ignore EVERYBODY, write a TRAGEDY, reach for the truth of life, aim high, write a masterpiece. Amaze + surprise them.’[ii]

I think Elyot wrote three masterpieces: My Night with Reg, The Day I Stood Still and Mouth to Mouth. Yes, they plough the same territory over and over: loneliness, friendship, music, memory, the passing of youth, betrayal, guilt, mortality, time. But these are the truths of life, and I can’t think of a writer I admire who, in the search for ultimate meaning, does not write about them.

At the Royal Court’s fiftieth anniversary celebrations, Roger Michell said of Reg that it arrived on his desk ‘almost perfectly formed: I cannot remember a single significant change that we made either during preparation or rehearsal. It is that odd thing, a most beautifully crafted and constructed modern play…’[iii]

Elyot’s papers reveal the sweat behind that perfection. He began the play as a sequel to Coming Clean, and it took him over a decade to let that idea fall away and find something new – a decade during which Aids changed everything for gay men, including Elyot, who told Gay Times in 1998, ‘One of the starting points for writing Reg was personal experience. I’ve suffered in similar ways to other gay men of my generation, experienced the same grief, loss and trauma.’[iv] He wrote many drafts, and my reading of the relevant correspondence is that Hampstead Theatre’s rejection of the play had a lot to do with ‘draft bog’ – that indissoluble problem in new writing. For a playwright, old drafts are discarded clay on the floor. But some early readers, even if they are the playwright’s champions, find their feet stuck in the bog.

Thankfully, Roger Michell and the Royal Court saw My Night with Reg as it stood before them, sculpted to perfection. 2024 is the play’s thirtieth anniversary, and the tenth anniversary of Elyot’s death. I hope it brings a revival of at least one of his six exquisite plays.

[i] University of Bristol Theatre Collection, KE/3/19/1, Book 1 of 6, p. 105.

[ii] UBTC, KE/3/26/1, Book 2 of 3, p. 58.

[iii] Roger Michell, in programme for Royal Court Theatre ‘Look Back: 50 Readings, 50 Writers, 50 Years’, My Night with Reg, 9 March 2006, UBTC, KE/3/19/11 (2 of 2).

[iv] Kevin Elyot to James Cary Parkes, ‘A comedy of terrors’, Gay Times, January 1998, pp. 16-17 (p. 17), UBTC, KE/3/23/5.

I agree with everything you say the masterly My Night With Reg is about. But I see the play more widely as the greatest play ever written about lies and lying – the pain and the necessity of it. Which is is why it endures.

Sorry, I’ve only just seen this. Oh yes indeed; one of Elyot’s great themes, in this play and others.